Ἡ μαρτυρία μας

Κάθε χρόνο, κατ' αὐτήν τήν ἡμέρα τῆς ἑορτῆς τῆς Ὀρθοδοξίας καλούμεθα νά κηρύξωμε, νά ἀπολογηθοῦμε γιά τήν πίστη μας, τή ζωή μας, τήν ταυτότητά μας καί τήν ἐλπίδα μας.

Στή σημερινή ἡμέρα, πού εἶναι ἡ γιορτή τῆς εἰκόνας καί ἡ ἑορτή τῆς εἰκόνας εἶναι ἡ γιορτή τοῦ ἀνθρώπου, εἰκόνας τοῦ Θεοῦ, ἔχουμε νά μαρτυρήσουμε περί τῆς Ἐκκλησίας ὡς πασχαλίου κοινότητος, πορευομένης πρός τό ὁριστικό πάσχα, περί τῆς Ἐκκλησίας ὡς Εὐαγγελικῆς καί Εὐχαριστιακῆς Κοινότητας, πού ἀναλαμβάνει στήν προσευχή της ὁλόκληρη τήν ἀνθρωπότητα καί τήν προσκαλεῖ νά λάβει μέρος στήν τριαδική ἀγάπη. Ὀφείλουμε νά μαρτυρήσουμε γιά τήν πνευματική σημασία τῆς γῆς καί τοῦ κάλλους, γιά τόν ἄνθρωπο σάν ὑπέρβαση καί κοινωνία, χαραγμένης μέ τήν εἰκόνα τοῦ Θεοῦ γιά τήν κλήση του, τή σπίθα, τήν πνοή πού τόν ἁρπάζει ἀπό αὐτόν τόν κόσμο καί τοῦ δίνει τήν δύναμη νά τόν μεταμορφώσει. Ἔχουμε νά μαρτυρήσουμε ὅτι ὁ Θεός εἶναι ἡ ἐλευθερία, ἡ χαρά καί ἡ ζωή τοῦ ἀνθρώπου καί ὅτι ὁ ἄνθρωπος μπορεῖ νά τόν γνωρίσει μέ μία ἀδιαχώριστη ἀπό τήν ἀγάπη γνώση, ἑνώνοντας τό πνεῦμα του καί τήν καρδιά του καί εὑρίσκοντας τήν καρδιά του στόν Χριστό, "καρδιά τῆς Ἐκκλησίας", ὅπως ἔλεγε ὁ ἅγιος Νικόλαος Καβάσιλας.

Το μυστήριο τῆς Ἐκκλησίας

Ὅταν γίνεται λόγος γιά τήν Ὀρθοδοξία, γίνεται λόγος γιά τό πολυτιμώτερο τῆς πίστης καί τῆς ἐλπίδας, τήν Ἐκκλησία, ἀλλά εἶναι δυνατό νά ὁριστῆ ἤ νά περιγραφῆ αὐτό πού μετέχει στό μυστήριο τοῦ Θεοῦ στή θεία ζωή, σ' αὐτήν τήν ἀνεξάντλητη ζωή τοῦ Θεοῦ πού γεμίζει τήν ἀνθρώπινη ὕπαρξή μας καί μέσα στήν ἁμαρτία μας καί μέσα στήν πτώση μας; Πῶς θά μποροῦσε νά μιλήσει κανείς γιά τήν Ἐκκλησία ἡ ὁποία ἐργάζεται ἀδιάκοπα γιά νά ἀναγάγει τόν ἄνθρωπο στήν προσωπική του καί ἐκκλησιαστική του ζωή στά σκαλοπάτια τῆς θέωσης;

Ἡ Ἐκκλησία εἶναι σῶμα Χριστοῦ, ἡ ἐν Ἁγίῳ Πνεύματι ἕνωση καί ἑνότητα τῶν πιστῶν στήν θεωμένη -δοξασμένη ἀνθρωπότητα τοῦ Χριστοῦ. Χριστός καί Ἐκκλησία εἶναι ἑνότητα ἀδιάσπαστη καί ἀσύγχυτη. Εἶναι, κατά τόν Ἱ. Χρυσόστομο, "γένος ἕνα, Θεοῦ καί ἀνθρώπων". Ὁ Χριστός εἶναι ὁ "ἐκκλησιαστής μας" γιατί μᾶς συνάγει στό Πανάγιο σῶμα Του ἀλλά καί ἡ Ἐκκλησία μας, γιατί γίνεται ὁ πνευματικός τόπος τῆς συνάξεώς μας. Νά γιατί δέν μπορεῖ νά ὑπάρξει ποτέ χωρίς τόν ἀληθινό Χριστό Ἐκκλησία, οὔτε πάλι νά στηριχθεῖ σέ καμμιά ἰδεολογία, ἔστω λεγομένη "Χριστιανική ". Γιατί εἶναι ἀδιάσπαστα συνυφασμένη μέ τό πρόσωπο τοῦ Θεοῦ Λόγου, τοῦ Σαρκωμένου Λόγου τοῦ Θεοῦ, τοῦ Σωτῆρος Χριστοῦ. Ἡ Ἐκκλησία εἶναι ὁ ἴδιος ὁ Χριστός, ὁ ὅλος Χριστός, ὄχι σῶμα Χριστιανῶν ἀλλά σῶμα Χριστοῦ.

Τήν χριστοκεντρική αὐτή πραγματικότητα τῆς ἐκκλησιαστικῆς κοινωνίας εἰκονίζει καί ἐκφράζει, ἀλλά καί πραγματώνει, μιά πράξη λειτουργική, πού λαμβάνει χώρα στό τέλος τῆς Θ. Λειτουργίας. Πρόκειται γιά τή συστολή τῶν Τιμίων Δώρων στό ἅγιο Ποητήριο. Ὁ Λειτουργός συστέλλει (συγκεντρώνει) μέσα τό ἅγιο Ποτήριο, ὅ,τι ἄλλο ὑπῆρχε στό Δισκάριο ἐκτός ἀπό τόν Ἀμνό, τό σῶμα τοῦ Κυρίου, δηλαδή τή μερίδα τῆς Θεοτόκου, τά τάγματα τῶν Ἀγγέλων καί Ἁγίων, τά μνημονευθέντα , ζῶντα καί τεθνεῶτα μέλη τοῦ Σώματος τοῦ Χριστοῦ, πού συνεπιτέλεσαν μέ τόν Λειτουργό τή Θεία Λειτουργία. Ἔτσι ἡ ἐν Χριστῷ κοινωνία τῶν πιστῶν εἶναι ἤδη συναγμένη μέσα στό ἅγιο Ποτήριο.

Ἡ καινή κτίση

Ἡ κοινωνία στό ὄνομα τοῦ Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ διαφοροποιεῖται ἀμετάκλητα καί ὁριστικά ἀπό κάθε ἄλλη ἐγκόσμια κοινωνία. Ὅλες οἱ ἀνθρώπινες κοινωνίες θεμελιώνονται σέ ὁρισμένες ἰδεολογικές προϋποθέσεις.

Ἡ κοινωνία τοῦ σώματος τοῦ Χριστοῦ εἰσῆλθε στόν κόσμο σάν καινούργια πραγματικότητα ὡς "Καινή Κτίσις". Τό πρόσωπο τοῦ Χριστοῦ τό κατ' ἐξοχήν καί μόνο "ν έ ο" πού γνώρισε ποτέ ὁ κόσμος διαφοροποιεῖ ριζικά τή δική του κοινωνία, ἀπό κάθε ἀνθρώπινη ὁμάδα πού διεκδικεῖ τό ὄνομα τῆς κοινωνίας.

Ἡ ἔνταξη μας ὅμως στήν ἐν Χριστῷ κοινωνία καί συνεπῶς στήν ἐκκλησιαστική ζωή προϋποθέτει ἕνα καί μοναδικό τρόπο. Εἶναι ἀπόλυτη ἀνάγκη ἡ ζωή τοῦ Χριστοῦ, ἡ χριστοζωή, σάν νέος τρόπος ὕπαρξης, νά γίνει καί δική μας ζωή. Αὐτό πραγματοποιεῖται, ὅταν μετά ὁρισμένη πορεία, φθάσουμε στό σημεῖο να μή ζοῦμε πιά ἐμεῖς, ἀλλά νά ζῆ μέσα μας ὁ Χριστός. Ὅλη αὐτή ἡ πορεία στή γλώσσα τῆς Ἐκκλησίας ὀνομάζεται πορεία θεώσεως καί εἶναι ἡ ἴδια ἡ σωτηρία. Στή ζωή τῆς Ἐκκλησίας εἰσέρχεται κανείς γιά νά σωθεῖ, νά θεωθεῖ. Ἄν ὁ στόχος αὐτός παραθεωρηθεῖ τότε ἀλλοιώνεται ἡ ἐκκλησιαστική ζωή καί ἔτσι καταντᾶ μιά αἵρεση πού δέν σώζει ἀλλά ὁδηγεῖ στήν ἀπώλεια.

Ἡ μεταπτωτική ἐμπειρία τοῦ κόσμου

Ἡ ἁμαρτία τοῦ κόσμου δέν θέλησε νά δεχθῇ τόν Χριστό ὡς κέντρο ὅλων τῶν γεγονότων. Οἱ συνέπειες ἀπό μιά τέτοια ἀποδοχή πού εἰσχωροῦν βαθειά στή ζωή καί ἐγείρουν μεγάλες ἀξιώσεις ἀλλοτριώνουν τελικά τόν ἴδιο τόν ἄνθρωπο κάνοντας τον νά λησμονήση τήν θεία του καταβολή καί τόν προορισμό του, ὅτι ὁ Θεός στό πρόσωπο τοῦ Υἱοῦ Του αὐτοπαραδόθηκε " ἵνα οἱ ἄνθρωποι ζωήν ἔχωσιν καί περισσόν ἔχωσιν".

Ἡ νεοελληνική μας ζωή πού πασχίζει ἀκόμη γιά τήν ἰδεολογική της ταυτότητα ἐμφανίζει τήν εἰκόνα μιᾶς κουλτούρας ἤ ἑνός νεοουμανισμοῦ στά ὅρια δῆθεν ἀνώδυνων ἰδεολογιῶν μέ τίς ὁποῖες ζητοῦμε νά ντύσουμε τήν προσωπική μας καί πνευματική μας φτώχεια.

Τό σκάνδαλο δέν εἶναι ἡ ἄρνηση τοῦ Θεοῦ, ἀλλά ὁ ἐγκλεισμός στήν ἐνδοκοσμιότητα τοῦ ἀνθρώπου. Δέν εἶναιἡ ἄρνηση κάθε μεταφυσικῆς ἀρχῆς ἀλλά ἡ σκοπιμότητα νά διασωθεῖ ἡ κυριαρχία τοῦ ἀνθρώπου στόν ἐξαντλούμενο κόσμο του. Δέν εἶναι ὁ λόγος τοῦ Σταυρῦ, ἀλλά ὁ λόγος τοῦ ἀνθρώπου πού αὐτοαναιρεῖται. Δέν εἶναι ἡ ἀπαίτηση τῆς ὑπερβάσεως, ἀλλα ἡ αὐθάδεια καί ἡ ἀνεπάρκεια τοῦ ἀνθρώπου. Δέν εἶναι ἡ ἔλλειψη δραστηριότητος, ἀλλα ἡ πολυπραγμοσύνη μας, ἡ τάση καί ἀναίδειά μας νά ἀσχολούμαστε μέ ὅλα καί νά τά ἐξηγοῦμε ὅλα. Τό σκάνδαλο ἀκόμη δέν εἶναι πῶς μιλοῦμε γιά τόν ἄνθρωπο, ἀλλά πώς μιλοῦμε γιά νά τόν ἀγνοοῦμε καί νά τόν ἀπορρίπτουμε.

Ἔτσι στό χῶρο τῆς μεταπτωτικῆς μας ἐμπειρίας θά πρέπει νά μιλοῦμε γιά τήν διαστροφή καί τό πρόβλημα τῆς ζωῆς καί τῆς ὕπαρξης ἔξω ἀπό τήν ζωή τῆς Ἐκκλησίας.

Ἔτσι τό τελικό νόημα τῆς σημερινῆς μας κρίσης εἶναι ὅτι ὁ κόσμος μέσα στόν ὁποῖο πρέπει νά ζήσει σήμερα ἡ Ὀρθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία δέν εἶναι ὁ κόσμος της, οὔτε ἀκόμη περισσότερο κάποιος οὐδέτερος κόσμος, ἀλλά ἕνας κόσμος πού τήν προκαλεῖ στήν οὐσία καί τήν ὕπαρξή της, ἕνας κόσμος πού προσπαθεῖ συνειδητά ἤ ἀσυνείδητα νά τή μετατρέψει καί νά τή μειώσει.

Τό ἐρώτημα συνεπῶς εἶναι εὐνόητο: τί μπορεῖ νά γίνει σήμερα;

Πρώτιστη ἀνάγκη εἶναι νά βιώνεται ἡ ἐσχατολογική αὐτοσυνειδησία τῆς Ὀρθοδοξίας καί στή σημερινή ἱστορική πραγματικότητα. Πῶς δηλαδή θά λειτουργήσουμε ὅλοι μαζί καί ἡ ἐκκλησιαστική μας ζωή, ὀρθόδοξα μέσα στά σημερινά πολιτικά - πολιτισμικά καί κοιωνικά δεδομένα. Αὐτή ἄλλωστε εἶναι ἡ στάση τῆς Ὀρθοδοξίας σέ κάθε ἐποχή! Διακρατεῖ τή συνέχεια της, ὄχι μέσῳ κάποιας συνοπτικῆς διασύνδεσης μέ τό παρελθόν, ἀλλά παροντοποιώντας τήν παράδοσή της στό κάθε παρόν, κινούμενη στό δικό της διαρκές παρόν ζωῆς και μαρτυρίας.

Καμμιά δυνατότητα ὅμως δυναμικῆς ἐπιστροφῆς στήν παράδοση τῆς ἐκκλησιαστικῆς μας ζωῆς δέν εἶναι δυνατή ἄν δέν ξεκαθαρισθεῖ πρῶτα τί ἐπιδιώκουμε. Ἄν δέν συνειδητοποιηθεῖ ἡ κατάστασή μας. Ἄλλωστε αὐτό συμβαίνει πάντα. Χωρίς συνειδητοποίηση τῆς ἁμαρτίας, ἡ μετάνοια εἶναι ἀδύνατη.

Θά μᾶς πεῖ κάποιος ὅτι ὅλα αὐτά σάν ἐπισήμανσεις καί θεωρία στέκουν. Στήν πράξη ὅμως τί γίνεται; Τό πρακτικώτερο εἶναι ἡ Χάρις τοῦ Θεοῦ, ἡ ὁποία ἀναπληρώνει καί θεραπεύει. Ζητεῖτε καί εὑρήσετε. Ἡ εὐαγγελική περικοπή πού διαβάζεται τήν Κυριακή τῆς Ὀρθοδοξίας μᾶς προσκαλεῖ καί μᾶς προκαλεῖ.

"Ἔρχου καί ἴδε". Καί ἄν αὐτός ὁ ἐρχομός μας εἶναι πορεία ταπεινή καί καθαρή, πού θά περνᾶ μέσα ἀπό τήν λατρευτική καί μυστηριακή ζωή τῆς ἐνορίας μας, τῆς Ἐκκλησίας μας, τότε θά ὁδηγηθοῦμε στήν ἑνότητα φρονήματος καί στήν ἐν Χριστῷ αὔξηση καί ἀναγέννησή μας, ὥστε ὁ καθένας ἀπό μᾶς νά μπορέσει νά πεῖ τοῦτο τό λόγο, ὅπως στό σημερινό Εὐαγγέλιο ὁ Ναθαναήλ:

" Ραββί, ἀληθῶς Θεοῦ υἱός εἶ".

ΥΠΟΣΗΜΕΙΩΣΕΙΣ

Βλ. Πρωτοπρεσβυτέρου Μιχαήλ Καρδαμάκη, Ὀρθόδοξη Πνευματικότητα, ἐκδ. Ἀκρίτας.

http://www.apostoliki-diakonia.gr/gr_main/catehism/theologia_zoi/themata.asp?contents=selides_katixisis/contents_MegaliSarakosti.asp&main=kat007&file=2.3.htm

Η ιστορία που ακολουθεί και κυκλοφορεί στο διαδίκτυο ως μια προσωπική εμπειρία, μπορεί να μην είναι αληθινή. Το μήνυμα όμως που μεταφέρει δεν μπορεί να αμφισβητηθεί από κανέναν.

«Όταν ήμουν παιδί, θυμάμαι πόσο λάτρευε η μαμά μου να μαγειρεύει για μένα και τον μπαμπά μου.

Θυμάμαι ένα συγκεκριμένο βράδυ που η μητέρα μου γύρισε στο σπίτι μετά από μια κουραστική μέρα στη δουλειά, την ώρα του δείπνου τοποθέτησε μπροστά στον μπαμπά μου ένα πιάτο στο οποίο υπήρχε μέσα μια φέτα ψωμί με μαρμελάδα και ένα εξαιρετικά καμένο τοστ.

Εγώ περίμενα πως ο μπαμπάς μου θα της κάνει παρατήρηση για το καμένο τοστ. Εκείνος όμως το πήρε στα χέρια του και τρώγοντας το, με ρώτησε πώς ήταν η μέρα μου στο σχολείο.

Δεν θυμάμαι τι του απάντησα εκείνο το βράδυ, αλλά θυμάμαι ότι άκουσα τη μαμά μου να ζητά συγγνώμη από τον μπαμπά μου για το καμένο τοστ. Αυτό που δεν θα ξεχάσω ποτέ όμως, ήταν η απάντηση του:

«Αγάπη μου, μου αρέσουν πολύ τα τοστ όταν είναι καμμένα».

Αργότερα εκείνο το βράδυ, πήγα να φιλήσω το μπαμπά μου για καληνύχτα και τον ρώτησα αν πράγματι του άρεσε τόσο πολύ το καμένο τοστ. Με τύλιξε στην αγκαλιά του και μου είπε:

«Η μαμά σου πέρασε μια πολύ δύσκολη μέρα στη δουλειά σήμερα και ήταν πολύ κουρασμένη. Και εκτός αυτού, ένα καμένο τοστ ποτέ δεν έβλαψε κανέναν. Τα σκληρά λόγια όμως πίκραναν πολλούς».

Ξέρετε, η ζωή είναι γεμάτη από ατελή πράγματα και ατελείς ανθρώπους. Δεν είμαι ο καλύτερος σε τίποτα και ξεχνώ τα γενέθλια και τις επετείους ακριβώς όπως κάνουν όλοι οι άλλοι. Αυτό που έχω μάθει όλα αυτά τα χρόνια, είναι να αποδέχομαι τα λάθη των άλλων και να γιορτάζω την διαφορετικότητα τους.

Είναι ένα από τα πιο σημαντικά κλειδιά για τη δημιουργία μιας υγιούς, αναπτυσσόμενης και μεγάλης διάρκειας σχέσης. Η ζωή είναι πολύ σύντομη για να ξυπνάτε μετανιωμένοι. Αγαπήστε τους ανθρώπους που σας αντιμετωπίζουν σωστά και δείξτε ευσπλαχνία σε αυτούς που δεν το κάνουν.

ΑΠΟΛΑΥΣΤΕ τη ζωή σας τώρα. Έχει ημερομηνία λήξης.»

Πηγή: https://iliaxtida.wordpress.com/2015/02/26/%CE%AF-%CF%8C-%CE%AC-io/#more-18595

Saint Nectarios of Aegina (1846–1920)

A saint’s icon can illustrate the story of his life in detail. Our reporter Ekaterina STEPANOVA asked the icon painter and teacher of St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University, Svetlana VASYUTINA, how we can tell by a saint’s sacred image what his occupation was and what he is famous for.

Notwithstanding Our Infirmities

The first question that an icon painter is often asked is how one can draw a saint one has never seen. When I graduated from the Surikov Institute of Art (Moscow), I was also tortured by this question. In hagiography, we find descriptions of many saints, for instance, a straight nose, a moustache, a black or a long beard… But there can be so many variants of a ‘long beard,’ how shall I understand what he really looked like? The answer is simple: it is the saint himself who helps the icon painter to determine the details. It is the only way. One is to read the hagiography, to pray to this saint, and then the sacred image will turn out correctly. If an icon painter paints an icon as a picture, trying to reflect a part of himself, his own feelings, his vision of the saint, he will fail. I remember when I was making a mosaic of Our Lady, it was not at once that the sacred image was shaped out. They told me to leave it as it was. But I could not stop until I suddenly felt that the image now was exactly what Our Lady wanted it to be. I won’t hesitate to say that it is the Holy Spirit who moves the icon painter. It is the Holy Spirit who draws the lines, chooses the colors.

There arises a second appropriate question. An icon painter is as sinful a man as any other, how can he draw with the Holy Spirit? This hard question is most of all acute for icon painters themselves. The only ‘way out of this situation’ is to fully realize one’s own passions, one’s numerous sins and one’s unworthiness, and pray to God asking for His help. I pray thus, ‘O Lord, you know I am unworthy. You know I can do nothing by myself. But I love people, I love You, O Lord! You do want people to pray to You, don’t You? Let me be your paintbrush. What do people care whether the paintbrush is plastic or wooden, if it is crooked or broken? But through me people will be able to see Your sacred image.’

Maybe I shouldn’t have disclosed the secrets of the icon painter’s inner life, but without this it is impossible to understand how sacred images appear. They come out in the very shape the saints want them to have. It happens not because of the icon painter’s virtues, but notwithstanding his infirmities.

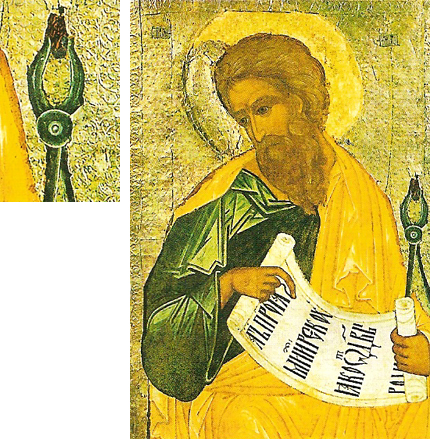

Three Pokers in Hand

An icon painter must see to it that a person, seeing the icon, should understand what the saint is famous for, what his life was like. It is a hard task. The colors, the background, the clothes – all matter.

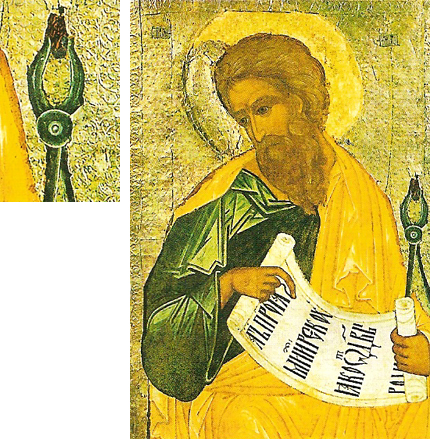

The icon painter’s task is to concentrate all the information about the saint (and this can be years or scores of years of ascetic life) in one little image that would reflect, as a symbol, all his lifetime. Often, the saints in icons would hold in their hands something they are celebrated for. For example, St. Sergius of Radonezh founded a monastery, therefore, he is drawn with the monastery on his palm. St. Great Martyr Panteleimon was a healer, and he holds a box with medicines in the icon. St. Andrei Rublyov is often portrayed with the Trinity Icon in his hands. Prelates and Evangelists are depicted with the Gospel in their hands. Holy Fathers often hold a rosary, like St. Seraphim of Sarov, or rolls with holy maxims or prayers, like St. Siluan Athonitul. Martyrs would hold a cross.

St. Prokopy of Ustug is portrayed holding three pokers in his hands. I was surprised to see this. I started reading his biography and found that St. Prokopy was ‘foolish in Christ,’ he would run about the town, rattling a poker in the air, or maybe even hitting people’s heads with it, and denounce people’s sins. Why three pokers? Icon painters told me that they draw three pokers to exaggerate the situation – it appears there is such a tradition! When I was working at the fresco with this saint in Optina Pustyn’ monastery, I painted every poker with different colors: the first one was green, the second one was red, and the third one was blue!

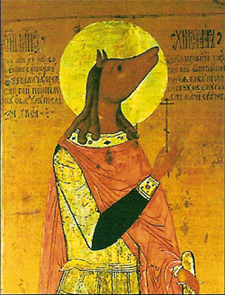

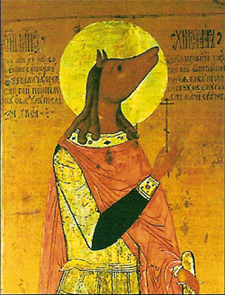

It is known that St. Martyr Christophor who lived in Egypt in the III century was very handsome. To flee temptations, he begged God to change his appearance, to make him repulsive. God granted his request. In icons, he is portrayed as having a dog’s head. I do not think he really had a dog’s head, though God can do anything, it is just to show that his appearance became ugly. They exaggerate this motive in icons in order to emphasize the saint’s deed and to focus the attention of the person praying before the icon.

It is known that St. Martyr Christophor who lived in Egypt in the III century was very handsome. To flee temptations, he begged God to change his appearance, to make him repulsive. God granted his request. In icons, he is portrayed as having a dog’s head. I do not think he really had a dog’s head, though God can do anything, it is just to show that his appearance became ugly. They exaggerate this motive in icons in order to emphasize the saint’s deed and to focus the attention of the person praying before the icon.

The color in icons plays an equally important role as the things mentioned above. Red belongs to martyrs. Blue stands for wisdom. White symbolizes paradise and chastity. Green is the color of the Venerable Fathers. Golden symbolizes sanctity. A while ago, I was tortured by the question why it is golden. Once I was standing at a church, looking at the iconostasis. Suddenly, they turned off the electric lights, and only candles before the icons were burning. The golden traces were shining, giving back the light. It was as if not the candles but the halos were radiating light. I was amazed; the light seemed not material, not as comes from a candle or a lamp. The golden color shows the person painted in the icon was granted a different kind of light.

Colors in Icons

Red is the color of blood and sufferings, the color of Christ’s sacrifice. Martyrs’ clothes in icons are painted red. Red are the wings of archangels and seraphims who are close to God’s throne. Red is the color of Resurrection, of life’s victory over death. Sometimes they would even have red backgrounds symbolizing the triumph of eternal life.

White is the symbol of Divine light. It is the color of chastity, simplicity, paradise. In icons and frescos, saints and the righteous men usually wear white clothes. Babies’ swaddles and angels are also white.

Blue means the endlessness of the heaven, the symbol of eternal world. It also symbolizes wisdom. Blue is supposed to be the color of Our Lady who united in herself the earthly and the heavenly.

Green is the color of nature, of life, grass, leaves, bloom, and youth. Earth is painted green. The color would be present where life starts: in Nativity scenes. The golden shine of mosaics and icons is the magnificence of the Heavenly Kingdom and sanctity.

Purple or crimson is a very meaningful color in the Byzantine culture. It is the color of the King, the Sovereign, the Lord in Heaven, the emperor on earth. This color can be seen in Our Lady’s clothes as she is the Queen of Heaven.

Brown is the color of bare earth, dust, anything temporary and perishable. Mixed with the royal purple in Our Lady’s clothes, this color reminds us of human nature, subject to death.

A color which is never used in icon painting is grey. It is the mixture of black and white, evil and goodness, and this is the color of uncertainty, emptiness and non-existence.

Black is the color of evil and death. In icon painting, this color is used to paint caves, as symbols of a grave, and the hellhole. In some plots, it can be the color of secrecy. Black clothes of monks who departed from the usual life symbolize the rejection of worldly pleasures and habits – death in one’s lifetime, in a sense.

Skies and Earth in Icons

In icons, two worlds co-exist: the celestial and the earthly one. The celestial means the heavenly, the supreme one. The word ‘earthly’ in Russian originates from the word ‘vale, valley’ and means something below. This is the principle of depicting images in icons. Saints’ figures stretch themselves high, their feet hardly touching the ground. In icon painting it is called ‘pozyom’ (‘manure’) and is usually painted green or brown.

Where Does a Taxi in the Icon Come From?

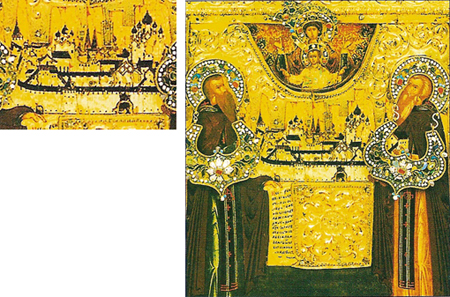

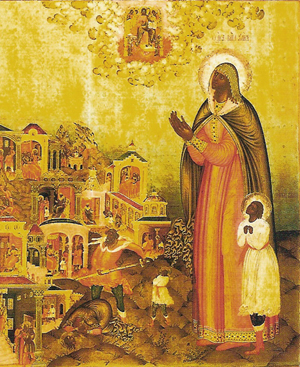

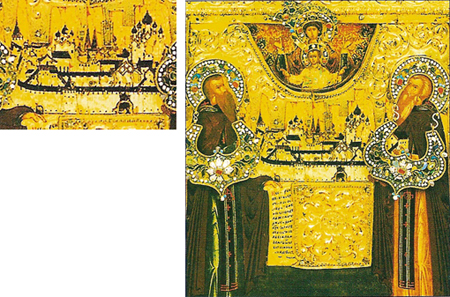

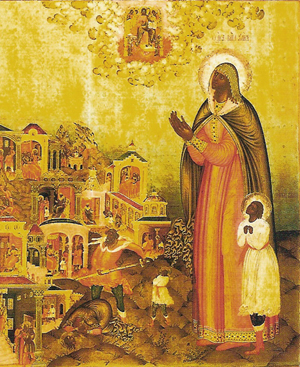

In the background of a saint’s icon they often paint the monastery, the forest, the cave where the saint lived, or the place that he specially patronizes. The synaxis of Kiev Pechersk saints is painted against the background of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra; St. Maria of Egypt is painted against the background of a desert; St. Blessed Ksenia – against St. Petersburg and the church at Smolenskoe graveyard. There exists a well-known icon of St. John of Shanghai in which one can see a pavement and a taxi. A remarkable icon! Someone can get confused; but say, if many centuries ago they could paint a desert, why can’t we paint a taxi now? We live in a historical period of time, in San Francisco they have this kind of pavement and yellow taxicabs can be seen around the city.

Such literary details appeared in icons to make them more understandable. A while ago there were lots of illiterate people who could ‘read’ the hagiography in a condensed form in the icon. There started to appear icons with ‘brands,’ which means that around the saint’s sacred image there would be drawn pictures illustrating the brightest episodes of his or her life. The saint’s ascetic deeds, his martyrdom and death, all the story of his life would be told in ‘pictures’ in one and the same icon. In the brands to the image ‘The Synaxis of All the Saints who Shone in Russian Land,’ one can even see the Red Army men shooting new martyrs, these men having no halos, of course.

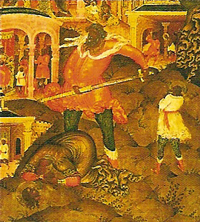

Past and Future in Icons Often an icon illustrates the events of several days or even the whole lifetime of a saint. The icon ‘Kirik and Ulita’ (XVII century) tells the story of mother and son in detail. Holding up their hands in prayer, the martyrs call to Heaven where on His golden throne amidst clouds sits Jesus Christ. On the left, among arcs and columns (that means within buildings) one can see scenes of their deeds, miracles and their deaths as martyrs. Thus the icon illustrates the past and the future.

But if someone in an icon or a fresco is painted without a halo it does not necessarily mean that he is an ‘unfavorable personage.’ For instance, in Serbia and Greece there is a tradition to paint frescos of church wardens, the philanthropists, and the embellishers of the church or the monastery. The Saviour sits on His throne, Our Lady and John the Baptist next to Him, and following them in modern clothes are the church wardens, the princes, carrying their gift to God – their prayers for their whole nation. In the icon ‘The Joy of All Who Sorrow,’ there are paupers, cripples, the sick, the mourning ones surrounding Our Lady entreating Her for help and intercession; however, they are all depicted without halos. And in the icon ‘The Lord’s Entry into Jerusalem,’ they depict playing children who are overwhelmed with joy, throwing up their clothes, pushing each other, with their shoelaces undone, with their hair unkempt, the donkey trotting over someone’s foot. It is done so as to make the spectator at least emotionally respond to what he or she sees. Naturally, it is the external, but through this there can appear the internal, the more profound, the spiritual.

Translated by Olga Lissenkova

Edited by Yana Samuel

Source. http://www.pravmir.com/what%E2%80%99s-the-difference-between-an-icon-and-a-portrait/

It is known that St. Martyr Christophor who lived in Egypt in the III century was very handsome. To flee temptations, he begged God to change his appearance, to make him repulsive. God granted his request. In icons, he is portrayed as having a dog’s head. I do not think he really had a dog’s head, though God can do anything, it is just to show that his appearance became ugly. They exaggerate this motive in icons in order to emphasize the saint’s deed and to focus the attention of the person praying before the icon.

It is known that St. Martyr Christophor who lived in Egypt in the III century was very handsome. To flee temptations, he begged God to change his appearance, to make him repulsive. God granted his request. In icons, he is portrayed as having a dog’s head. I do not think he really had a dog’s head, though God can do anything, it is just to show that his appearance became ugly. They exaggerate this motive in icons in order to emphasize the saint’s deed and to focus the attention of the person praying before the icon.