Saint Nectarios of Aegina (1846–1920)

A saint’s icon can illustrate the story of his life in detail. Our reporter Ekaterina STEPANOVA asked the icon painter and teacher of St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University, Svetlana VASYUTINA, how we can tell by a saint’s sacred image what his occupation was and what he is famous for.

Notwithstanding Our Infirmities

The first question that an icon painter is often asked is how one can draw a saint one has never seen. When I graduated from the Surikov Institute of Art (Moscow), I was also tortured by this question. In hagiography, we find descriptions of many saints, for instance, a straight nose, a moustache, a black or a long beard… But there can be so many variants of a ‘long beard,’ how shall I understand what he really looked like? The answer is simple: it is the saint himself who helps the icon painter to determine the details. It is the only way. One is to read the hagiography, to pray to this saint, and then the sacred image will turn out correctly. If an icon painter paints an icon as a picture, trying to reflect a part of himself, his own feelings, his vision of the saint, he will fail. I remember when I was making a mosaic of Our Lady, it was not at once that the sacred image was shaped out. They told me to leave it as it was. But I could not stop until I suddenly felt that the image now was exactly what Our Lady wanted it to be. I won’t hesitate to say that it is the Holy Spirit who moves the icon painter. It is the Holy Spirit who draws the lines, chooses the colors.

There arises a second appropriate question. An icon painter is as sinful a man as any other, how can he draw with the Holy Spirit? This hard question is most of all acute for icon painters themselves. The only ‘way out of this situation’ is to fully realize one’s own passions, one’s numerous sins and one’s unworthiness, and pray to God asking for His help. I pray thus, ‘O Lord, you know I am unworthy. You know I can do nothing by myself. But I love people, I love You, O Lord! You do want people to pray to You, don’t You? Let me be your paintbrush. What do people care whether the paintbrush is plastic or wooden, if it is crooked or broken? But through me people will be able to see Your sacred image.’

Maybe I shouldn’t have disclosed the secrets of the icon painter’s inner life, but without this it is impossible to understand how sacred images appear. They come out in the very shape the saints want them to have. It happens not because of the icon painter’s virtues, but notwithstanding his infirmities.

Three Pokers in Hand

An icon painter must see to it that a person, seeing the icon, should understand what the saint is famous for, what his life was like. It is a hard task. The colors, the background, the clothes – all matter.

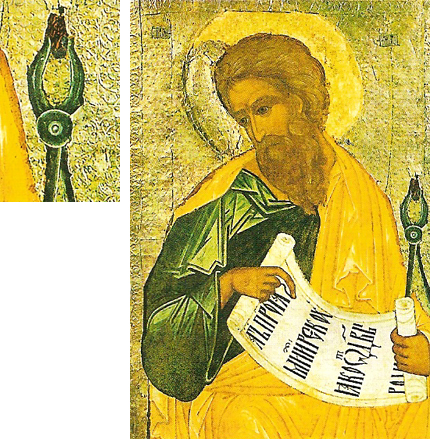

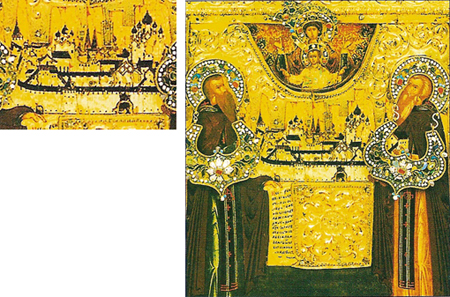

The icon painter’s task is to concentrate all the information about the saint (and this can be years or scores of years of ascetic life) in one little image that would reflect, as a symbol, all his lifetime. Often, the saints in icons would hold in their hands something they are celebrated for. For example, St. Sergius of Radonezh founded a monastery, therefore, he is drawn with the monastery on his palm. St. Great Martyr Panteleimon was a healer, and he holds a box with medicines in the icon. St. Andrei Rublyov is often portrayed with the Trinity Icon in his hands. Prelates and Evangelists are depicted with the Gospel in their hands. Holy Fathers often hold a rosary, like St. Seraphim of Sarov, or rolls with holy maxims or prayers, like St. Siluan Athonitul. Martyrs would hold a cross.

St. Prokopy of Ustug is portrayed holding three pokers in his hands. I was surprised to see this. I started reading his biography and found that St. Prokopy was ‘foolish in Christ,’ he would run about the town, rattling a poker in the air, or maybe even hitting people’s heads with it, and denounce people’s sins. Why three pokers? Icon painters told me that they draw three pokers to exaggerate the situation – it appears there is such a tradition! When I was working at the fresco with this saint in Optina Pustyn’ monastery, I painted every poker with different colors: the first one was green, the second one was red, and the third one was blue!

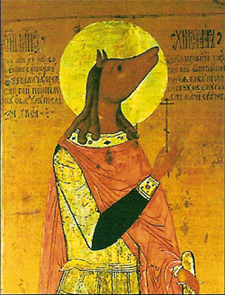

It is known that St. Martyr Christophor who lived in Egypt in the III century was very handsome. To flee temptations, he begged God to change his appearance, to make him repulsive. God granted his request. In icons, he is portrayed as having a dog’s head. I do not think he really had a dog’s head, though God can do anything, it is just to show that his appearance became ugly. They exaggerate this motive in icons in order to emphasize the saint’s deed and to focus the attention of the person praying before the icon.

It is known that St. Martyr Christophor who lived in Egypt in the III century was very handsome. To flee temptations, he begged God to change his appearance, to make him repulsive. God granted his request. In icons, he is portrayed as having a dog’s head. I do not think he really had a dog’s head, though God can do anything, it is just to show that his appearance became ugly. They exaggerate this motive in icons in order to emphasize the saint’s deed and to focus the attention of the person praying before the icon. The color in icons plays an equally important role as the things mentioned above. Red belongs to martyrs. Blue stands for wisdom. White symbolizes paradise and chastity. Green is the color of the Venerable Fathers. Golden symbolizes sanctity. A while ago, I was tortured by the question why it is golden. Once I was standing at a church, looking at the iconostasis. Suddenly, they turned off the electric lights, and only candles before the icons were burning. The golden traces were shining, giving back the light. It was as if not the candles but the halos were radiating light. I was amazed; the light seemed not material, not as comes from a candle or a lamp. The golden color shows the person painted in the icon was granted a different kind of light.

Colors in Icons

Red is the color of blood and sufferings, the color of Christ’s sacrifice. Martyrs’ clothes in icons are painted red. Red are the wings of archangels and seraphims who are close to God’s throne. Red is the color of Resurrection, of life’s victory over death. Sometimes they would even have red backgrounds symbolizing the triumph of eternal life.

White is the symbol of Divine light. It is the color of chastity, simplicity, paradise. In icons and frescos, saints and the righteous men usually wear white clothes. Babies’ swaddles and angels are also white.

Blue means the endlessness of the heaven, the symbol of eternal world. It also symbolizes wisdom. Blue is supposed to be the color of Our Lady who united in herself the earthly and the heavenly.

Green is the color of nature, of life, grass, leaves, bloom, and youth. Earth is painted green. The color would be present where life starts: in Nativity scenes. The golden shine of mosaics and icons is the magnificence of the Heavenly Kingdom and sanctity.

Purple or crimson is a very meaningful color in the Byzantine culture. It is the color of the King, the Sovereign, the Lord in Heaven, the emperor on earth. This color can be seen in Our Lady’s clothes as she is the Queen of Heaven.

Brown is the color of bare earth, dust, anything temporary and perishable. Mixed with the royal purple in Our Lady’s clothes, this color reminds us of human nature, subject to death.

A color which is never used in icon painting is grey. It is the mixture of black and white, evil and goodness, and this is the color of uncertainty, emptiness and non-existence.

Black is the color of evil and death. In icon painting, this color is used to paint caves, as symbols of a grave, and the hellhole. In some plots, it can be the color of secrecy. Black clothes of monks who departed from the usual life symbolize the rejection of worldly pleasures and habits – death in one’s lifetime, in a sense.

Skies and Earth in Icons

In icons, two worlds co-exist: the celestial and the earthly one. The celestial means the heavenly, the supreme one. The word ‘earthly’ in Russian originates from the word ‘vale, valley’ and means something below. This is the principle of depicting images in icons. Saints’ figures stretch themselves high, their feet hardly touching the ground. In icon painting it is called ‘pozyom’ (‘manure’) and is usually painted green or brown.

Where Does a Taxi in the Icon Come From?

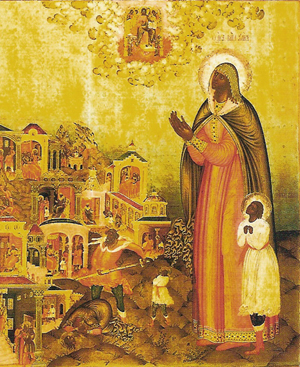

In the background of a saint’s icon they often paint the monastery, the forest, the cave where the saint lived, or the place that he specially patronizes. The synaxis of Kiev Pechersk saints is painted against the background of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra; St. Maria of Egypt is painted against the background of a desert; St. Blessed Ksenia – against St. Petersburg and the church at Smolenskoe graveyard. There exists a well-known icon of St. John of Shanghai in which one can see a pavement and a taxi. A remarkable icon! Someone can get confused; but say, if many centuries ago they could paint a desert, why can’t we paint a taxi now? We live in a historical period of time, in San Francisco they have this kind of pavement and yellow taxicabs can be seen around the city.

Such literary details appeared in icons to make them more understandable. A while ago there were lots of illiterate people who could ‘read’ the hagiography in a condensed form in the icon. There started to appear icons with ‘brands,’ which means that around the saint’s sacred image there would be drawn pictures illustrating the brightest episodes of his or her life. The saint’s ascetic deeds, his martyrdom and death, all the story of his life would be told in ‘pictures’ in one and the same icon. In the brands to the image ‘The Synaxis of All the Saints who Shone in Russian Land,’ one can even see the Red Army men shooting new martyrs, these men having no halos, of course.

Past and Future in Icons Often an icon illustrates the events of several days or even the whole lifetime of a saint. The icon ‘Kirik and Ulita’ (XVII century) tells the story of mother and son in detail. Holding up their hands in prayer, the martyrs call to Heaven where on His golden throne amidst clouds sits Jesus Christ. On the left, among arcs and columns (that means within buildings) one can see scenes of their deeds, miracles and their deaths as martyrs. Thus the icon illustrates the past and the future.

But if someone in an icon or a fresco is painted without a halo it does not necessarily mean that he is an ‘unfavorable personage.’ For instance, in Serbia and Greece there is a tradition to paint frescos of church wardens, the philanthropists, and the embellishers of the church or the monastery. The Saviour sits on His throne, Our Lady and John the Baptist next to Him, and following them in modern clothes are the church wardens, the princes, carrying their gift to God – their prayers for their whole nation. In the icon ‘The Joy of All Who Sorrow,’ there are paupers, cripples, the sick, the mourning ones surrounding Our Lady entreating Her for help and intercession; however, they are all depicted without halos. And in the icon ‘The Lord’s Entry into Jerusalem,’ they depict playing children who are overwhelmed with joy, throwing up their clothes, pushing each other, with their shoelaces undone, with their hair unkempt, the donkey trotting over someone’s foot. It is done so as to make the spectator at least emotionally respond to what he or she sees. Naturally, it is the external, but through this there can appear the internal, the more profound, the spiritual.

Translated by Olga Lissenkova

Edited by Yana Samuel

Source. http://www.pravmir.com/what%E2%80%99s-the-difference-between-an-icon-and-a-portrait/