Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Knowing God in all things

True joy comes from seeing God in all things, knowing God in all things. To know of God in the wisdom of the mind, this brings shimmers of peace and a foretaste of joy. Yet such joy is bounded, able to be swayed; for he who knows God’s presence but in part, still is able to imagine His absence. One, who sees God only in this place or in that, sees Him missing from those places in between. His joy is fleeting, for as in a moment it arises in the perception of God’s presence, so it retreats in the illusion of His absence.

The one whose joy is stable, solid and penetrating, is he who knows of God’s presence among all things, with all things, and in all things. Even as in the temple, so, too, in the school. Even as in the Church, so, too, in the field. From the brightest star to the smallest blade of grass, he sees the beautiful mystery of Christ present as all in all. He beholds the leaf with reverence, as the vessel of his direct encounter with the grace of God. He beholds his sister with love, seeing in her the energies of the blessed Divinity. He begins to see God present in more and more, and absent from less and less; until he comes to the divine realization that there is no place that God is not, that the whole of creation around him shimmers in radiance with the presence of the Most Holy. He understands that perceptions of God’s absence are but an illusion in which there is no truth.

Then is joy most full, most pure. Then it is unfailing, for in all things is God encountered; and where God is, there true joy also abides. Even in sorrow, joy is known; for the earth itself cries out in witness of Christ’s presence in the sorrow — of the divine love that pervades even the deepest human grief. In loneliness, one too finds joy: for all creation sings of the Creator’s grace, and through it the Creator Himself is present, reaching out to His children.

Behold God the all-present, all-loving, all-merciful Father, everywhere existing and ever the same. Behold the source and giver of joy, abounding in this world of life. Behold God indeed, who has the power to save and the compassion to redeem.

A Soul that is unstable can easily fall. ( St. Theophan the Recluse )

“…Timidity leads the soul into confusion and a certain unsteadiness, and a soul which is unstable can very easily fall. Yet self-satisfaction and conceit are the very enemies which one has to fight. Anybody who has let them in has fallen already, and is predisposed to further falls because they make a man inactive and negligent.

The warfare has begun. Guard your heart particularly, and do not let sinful impulses that arise reach your feelings. Meet each impulse as it enters your soul, and try to strike them all down. Be swift to establish firm convictions in your soul that are contrary to those to which your disturbing thoughts cling. These convictions will not only be your shield, they will also serve as arrows in your inner warfare. They not only defend your heart, but strike the heart of the enemy.

From this point on, the sin which arises will constantly be corrected by opposing thoughts and ideas. One must take care not to weaken or an instant, then victory will be sure, because the sinful impulse will have no firm support, but how long this will take will depend upon circumstances.”

~St. Theophan the Recluse

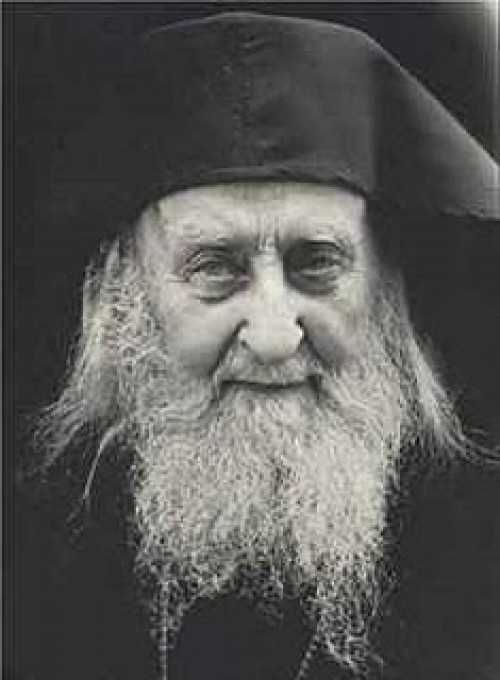

The last days of Elder Sofronios of Essex

Four days before he died, he closed his eyes and did not want to talk to us anymore. His face was radiant but not sad; full of tension. He had the same expression like when he was ministering the Devine liturgy. He would not open his eyes, or utter any words, but he would lift up his hand and bless us. He was blessing us without words but I knew that he was going away. Before, I used to pray that God should let him leave longer, just as we pray during the liturgy of St. Vasilios: “prolong the time of the old”. However during those days, when I knew he was leaving, I started praying: “My Lord, give your servant a rich welcome into your Kingdom”. I was praying using St Peter’s words, as we read it in his second letter. (2 Peter 11)

Thus I was praying intensely: “Please God give your servant a rich entry into your Kingdom and place him among his Fathers”. Then, I would call the names of all his brothers, ascetics, in Ayio Oros, whom I knew he had connections with, beginning with Saint Silouanos and then all the others. …On the last day, I went to visit him at six in the morning. It was Sunday and I was ministering the morning service, while Father Kyrillos and the other priests would minister the second service. I realized that he was going to leave us that day. I began the service at Ayia Prothesi. At seven o’clock the Hours would start, followed by the Devine Liturgy. I only uttered the prayers of Anaforas, because at our monastery we say these aloud. For the rest of the time, I continued to pray: “Lord give your servant a rich welcome”.

That service was different from all the others. When I called out: “The Holy to the Saints”, father Kyrillos came into the Sanctuary. We looked at each other; he began to cry and I realized that Fr Sofronios was gone. I asked him what time he died and I knew that he passed away during the time I was reading the Gospel. I stepped aside because he wanted to speak to me and he said: Give the Holy Communion to the faithful and then announce that Fr Sofronios has passed away , then minister the first Trisagio; I will also do this during the second service. Thus, I took the Holy Communion myself and then offered it to the faithful. Then I finished the service. I still do not know how I managed this. Afterwards, I went out of the Sanctuary and told those present: “My beloved brothers, our Christ, our Lord, is the wonder of God in all generations of our times, because in His words we find salvation and a solution to every human problem. Now we must do what the Devine Liturgy teaches us: to give thanks, to pray and to plead. Thus, let us thank God because he gave us such a Father , and let’s pray for his soul. “Blessed be our Lord” and thus I began the Trisagio.

We placed his body inside the church because the tomb had not been built yet. We allowed his body to remain uncovered for four days and we were constantly reading the Gospels from the beginning to the end, and then again, as it is customary to do when priests have passed away. We continued with several Liturgies, and he was there in the middle of the church for four days. It felt like Easter! It was such a wonderful and blessed atmosphere! No one came into hysterics, everyone prayed with inspiration.

I have a friend, Archimindrite, who used to spend several weeks at the monastery during the summer, Fr Ierotheos Vlachos, who wrote “A night at the desert of Ayio Oros”. He is now a Bishop of Nafpaktos. He arrived as soon as he learnt that Fr Sofronios was gone. He felt the same veneration and said to me: “If Fr Sofronios is not a Saint, then there are no Saints”.

It so happened that some monks from Ayio Oros were present as well, because they had come to see him but did not see him alive. Fr Tychon from Simonopetra was one of them. Every time Greeks would visit England for medical reasons, they would come to the monastery so that Fr Sofronios would bless them; many had been cured this way. During the third or fourth day of his passing, a family of four arrived at the monastery. They had a child of thirteen. He had a tumor in the brain and his operation was scheduled for the next day.

Fr Tychon said to me: “These people are very upset because they came and did not find Fr Sofronios alive”. Why don’t you read some prayers for the child?”

I said to him: “Let’s go together. You read from the book and we will read some prayers together at the other Chapel. We did just that and at the end Fr Tychon said to me: “You know something? Why don’t you pass the child under Fr Sofronios’ coffin? He will be cured. We are messing about reading prayers”. I answered that we couldn’t do this, because people would say that as soon as he had died we are trying to promote his sanctification. “You do it”, I said. “You are a monk from Ayio Oros. No one will say anything”.

He took the child by the hand and passed him under the coffin. The next day he was operated upon and the doctor found nothing. He closed up the brain and said: “It was a wrong diagnosis. It was probably an inflammation”. A Greek doctor was also accompanying the child and was carrying the x ray documents, which showed the tumor. He said to them: “I am sure you know very well what this ‘wrong diagnosis’ means”.

That child is now 27 years old and in a very good health.

Archim. Zacharias

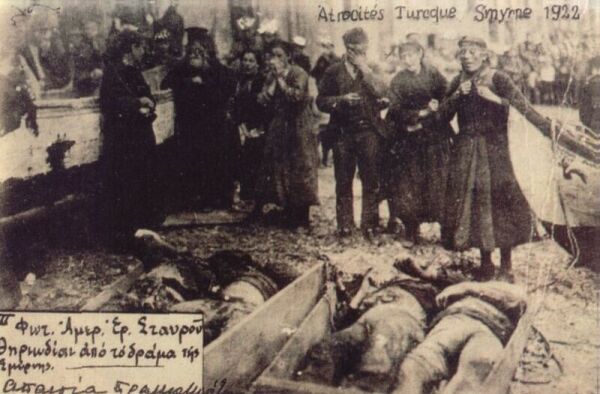

Smyrna 1922

Jihad has killed over 60,000,000 Christians. The destruction of the Christians in Smyrna is told here. Islam attacked the Christians of Smyrna in 1922. It was an annihilation that took place as the Christian Europeans stood aside. Before jihad exploded out of Arabia, Turkey (Asia Minor) was a Christian nation of primarily Greek culture called Anatolia. Today Turkey is 99.7% Islamic and increasing. How did this happen?

Islam tried for centuries to crush Christianity and the Greek culture in Turkey. Constantinople, the capital, fell to jihad in 1453. Christians became dhimmis, second-class citizens. The slow grind of discrimination was punctuated by outbursts of violence. Christian Greek Anatolia was painfully changed into Islamic Turkey.

The background for these stories is that in World War I Turkey sided with the Germans (Islam sided with the Nazis in WWII). In this political chaos, Kamal Attaturk rose to power as head of the military and political government. The Allies were exhausted and did not want to get involved with another war, so they gave money to support the Greeks to fight the Turks. Long story made short, the Greeks lost.

The old Ottoman empire had fallen and a new government was arising. The leader, Attaturk, was determined to destroy the last of the kafirs in Turkey. But what he talked about to the Westerners was the possibility of business in a new country. World War I was over and America was becoming a world power. America wanted trade and influence.

The war had brought about new technology and a fusion between industry and government. A concept called Dollar Diplomacy was practiced. Trade and diplomacy became two ends of the same stick. To show how far this concept went, the American ambassador took the funds that had been raised by Christians to help the Armenians persecuted in northern Turkey and gave it to the Turks. When the Christians protested to the media, the media would not report it because of State department pressure.

The Muslim Turks killed both Greeks and Armenians that day, but this lesson will focus on the murder and theft of the Armenians. Armenia was one of the first Christian nations and has suffered monstrously at the hands of Islam. Armenia was well educated and prosperous and had always been especially despised by Islam.

Over a million Armenians were killed in Turkey in the 20th century. There are two forms of evil in this story. The first evil is what was done by jihad. The second evil was what was not done by the dhimmi kafirs.

As you read this story of the destruction of Smyrna, know that this same story is repeated today by the same players and with the same results.

It starts

Smyrna was in what was once called Asia Minor, also Anatolia. It was one of the oldest communities of Christians left in Turkey. Islam had already destroyed the other six.

Revelation 1:11 saying, “What you see, write in a book and send to the seven assemblies: to Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and to Laodicea.”

Smyrna, Turkey, in 1922 was a dazzling city. It was a fusion of Christian, Armenian, Greek, and Mediterranean, with some Muslims. (It was like Beirut, Lebanon, before it fell to jihad. All multicultural politics that includes Islam will fall to Islam. There have never been any exceptions.)

The West had given the Greeks the responsibility of containing the Turkish army and then turned around and prevented its victory by interference. Now the Turks, lead by Attaturk [a Muslim military leader who became ruler], began to enter the city.

The Armenians were afraid. They had experienced Islam in their old homeland in northern Turkey where the Turkish genocide had killed their ancestors. There were many warships from England, America, France and Italy in the harbor. Large numbers of commercial freighters were there from every country. The Armenians began to crowd down to the harbor.

None of the freighters would take them on. They, along with the Allied warships in the harbor, were declared to be neutral and did not want to interfere with the politics of the rising Turkish power. They were in Smyrna for business and refugees were political. Other Armenians were unafraid; they believed that the warships from Christian nations would protect them.

Thirteen lessons on islam for christians

The Turkish army entered Smyrna and began to loot the shops of the Greeks and the Armenians. Then the army turned from looting to armed robbery. Then the Turks began to rob and kill the Armenians.

Aboard the American ship Litchfield, Captain Hepburn wrote that the Turks deserved high marks for discipline and high military standards. The cover-up had started.

The Turkish army surrounded the Armenian quarter and all Muslims were told to leave the area.

Killing the christian leader

Chrysostomos was the leader of the Orthodox Christians and went to see the local commanding officer to try to arrange the evacuation of Christians. He approached the general and extended his hand. The general spit on him. He pushed Chrysostomos out the door and yelled at the Muslim crowd, “Treat him as he deserves.”

The crowd dragged him down the street until they reached a barbershop.

Chrysostomos needed a shave the crowd decided. They pulled his beard out and rubbed dog excrement on him. The man with the straight razor cut off an ear and, at the sight of blood, the mob went mad trying to get close to Chrysostomos, who was barely able to murmur, “Receive my soul into Thy Kingdom, O Lord,” before he died. They cut out his eyes, ears and nose.

There were French marines standing by and their officer forbade them to defend the Christian. The body was dragged further down the street, when they stopped and cut off his privates and put them in his dead mouth.

When they reported his murder to the French Admiral Dumesnil, he said, “He got what was coming to him.”

Nowhere to run

In the harbor small boats carried refugees to the ships. No one would let them come aboard. When people jumped into the water and clutched the lines, the sailors cut the lines and poured boiling water on the people.

They would not break their “neutrality”. Turkish forces now moved house to house in the Armenian quarter.

They broke down the doors and robbed the men. The Muslim men brutally violated the women and then pushed them naked into the streets. Men were tied together to be marched outside the city and killed. Orders went out to use the sword and stop shooting the men. The guns were too noisy, and at the time, the Turks insisted nothing was happening. As many as a hundred men were lashed at the wrists and beheaded.

Lieutenant Merrill, an American, wrote to Admiral Bristol (the top American official in Turkey) that, “No one could imagine without seeing them under fire what a chicken-livered lot the Christian minorities (Greek and Armenian) are.”

Major Davis of the Red Cross cabled Admiral Bristol that the refugees must be evacuated. The Turks were going to solve their “race” problem by annihilation.

The American consul was exhausted. He was constantly besieged by Armenians who told the same story of murder and theft. Captain Hepburn sent for the Turkish army to drive them away from the Consulate.

Later that day, he boarded the Litchfield. He sat and watched as two newsmen typed up their reports. One of them stopped and read what he had written. He threw it into the wastebasket and said he could not send it in.

It would ruin his ability to report in Turkey after this was over. The other reporter agreed that they should dig up some old stories how the Greek Orthodox Christian soldiers had committed wrongs against the Turks.

They were desperate for something to offset the evil of jihad. And they did. The news wires were filled with reports of Greeks and Armenians looting before the Turkish troops arrived. They emphasized the discipline of the Turkish troops.

But not everyone lied:

‘The Armenian quarter is a charnel house ,’ a French officer noted on 13 September: ‘In three days this rich quarter is entirely ravaged. The streets are heaped with mattresses, broken furniture, glass, torn paintings. Some young women and girls, especially pretty ones, have been taken away and put into a house that is guarded by [Muslim] Turkish sentries. They must submit to the whims of the patrols. One sees cadavers in front of the houses. They are swollen and some have exposed entrails. The smell is unbearable and swarms of flies cover them. Day and night I make a tour of this quarter, and women who are crazed join me in the street; their clothes torn, their hair flying wild, they attach themselves to me. They beg me to take them from this quarter. First there are four, then eight, then a dozen and the number of women grows. I am in uniform and just about the only one to circulate on foot. Where to take them? Everywhere is filled:

Smyrna, 1922, M H Dobkin, Newmark Press, NY, NY, 1989, pg. 136.

A charnel house is a place where bodies are deposited.

Thirteen lessons on islam for christians

The churches, the schools, the Alliance Francaise are overflowing. So I disengage myself and try to reassure them. There are no men in this quarter; all are dead, or hiding, or they have been taken away. The New York Times reported that Attaturk was punishing any soldier who violated his orders to respect life and property.

Business is business

In Constantinople Admiral Chester and his two sons saw that a lifetime dream was to be fulfilled. His Ottoman-American Development Company would obtain a 99-year contract to all the sand and gravel for road building and all right-of-way needed from quarries. All imports would be exempt from duties and taxes.

He had written in Current History that the Turks had been falsely accused during the World War. They had been benevolent to the Armenians and other minorities.

Admiral Bristol was encouraging American businessmen to get in on the deals before the Europeans got the contracts.

Now the fire

The Turks now started to bring in kerosene. Sacks of “food” turned out to be gunpowder and dynamite. Wagons filled with barrels of gasoline were brought in. The winds shifted away from the Muslim quarter and the fires started.

As the firemen would be trying to put out the fires in one house, the Muslims were pouring gasoline in the next house. ‘In all the houses I went into I saw dead bodies,’ Tchorbadjis [a French officer] said. ‘In one house I followed a trail of blood that led me to a cupboard. My curiosity forced me to open this cupboard—and my hair stood on end. Inside was the naked body of a girl, with her front cut off.

At another house there was a girl hanging from a lemon tree in the yard. There were plenty of armed soldiers going about. One of them went in where there was an Armenian family hiding and massacred the lot. When he came out his scimitar was dripping with blood. He cleaned it on his boots and leggings.

‘On one of the roads I saw a man about forty-five or fifty years old. The Turks had blinded him and cut off his nose and left him on the streets. He was crying out, in Turkish, “Isn’t there anyone here Christian enough to shoot me so that I will not get burnt in the fire ?”

In the end, the entire Armenian quarter was burned. Some of the survivors were able to be evacuated.

Wrapping up the news

Admiral Bristol’s biggest headache of the moment was the press. Eyewitnesses arriving at foreign ports were already giving out spectacular news stories to reporters, and it seemed inevitable that after the mass exodus there would be a barrage of uncontrollable publicity. On 22 September the Admiral had cabled the State Department urging the release of an official account to offset ‘exaggerated and alarming reports appearing in American newspapers regarding Smyrna fires’. He offered a sample which the State Department was pleased to use:

American officers who have been eyewitnesses of all events occurring, Smyrna, from time of the occupation of that city by Nationalists up to present, report killings which occurred at that city were ones for the most part by individuals or small bands of rowdies or soldiers, and that nothing in the nature of a massacre had occurred. During the fire some people were drowned by attempting to swim to vessels in harbor or by falling off the quay wall, but this number was small. When masses of people were gathered on quay to escape fire, they were guarded by Turkish troops but were at no time prevented by such troops from leaving the quay if they so desired. It is impossible to estimate the number of deaths due to killings, fire, and execution, but the total probably does not exceed 2,000.

Bristol’s tone suited the policy makers. In the next issue of Foreign Affairs Elihu Root, (Secretary of State) was pleading for “restraint of expression”, noting that “nations are even more sensitive to insult than individuals”.

As far as the estimate that 2,000 died, 190,000 Armenians were never accounted for.

Christian martyrs

The deaths alone are a tragedy, but the supreme tragedy is that they have all died in vain. Every Christian knows about the number of Jews killed by Hitler, but what Christian knows about the deaths of their own?

Why did the Muslims do this? It was a sacred act. It is strictly according to the code of jihad that is laid out in the Koran and the Sunna [see the Ethics chapter]. Indeed, murder and theft of the kafir in jihad is a sacrament.

If one of the Muslim jihadists had been killed, he would be declared a martyr. The sword of the jihadist is the scalpel of Allah; it is pure good. Just as a scalpel removes what harms the body, jihad, in all its forms, removes what is offensive to Allah. The Muslims who did these acts were “good and moderate” Muslims. Mohammed did these things and he defines moderation and righteous action. A jihadist is a Mohammedan.

The great stain on Christianity is that those who sought to follow Christ suffered death and destruction under jihad and they had no support of the Christian community. When a mosque is even chipped by a kafir every Muslim roars in unity.

When the Muslims desecrated the church in Bethlehem in the late 20th century, the silence of Christians was deafening.

The final lesson

The mind of those who aided Islam in Smyrna by ignoring the suffering of the victims of jihad is dhimmitude. Yes, they were greedy, but they also did not have any any knowledge about the doctrine and history of political Islam. The businessmen, diplomats, and military men were clueless about the real evil happening and how it was just the next step tofurther suffering.

It is not that Islam is so strong, but that kafirs are so weak. Ignorance of the doctrine and history of political Islam blinds the kafirs. Today, the Armenians are trying to tell their story, but no one cares, no one listens. Turkey denies the annihilation and is trying to become a part of the European Union. No one wants to talk about what could be bad for business, so the EU does not want to talk about it. It upsets the Muslims.

The punished angel

An elder once said that there was this hermit who was living in the deepest desert for many years and had achieved the visionary charisma to such an extent that he was also in company with angels. Then this is what happened:

An elder once said that there was this hermit who was living in the deepest desert for many years and had achieved the visionary charisma to such an extent that he was also in company with angels. Then this is what happened: Two brothers, monks, heard about this hermit and wished to meet him so that they could benefit from his acquaintance. They abandoned their cells and headed towards the deserted looking for this servant of God, having in their hearts total confidence in him.

A few days later, they reached the hermit’s cave. While they were some distance away, they saw a man dressed in white, standing on one of the hills next to the hermit’s cave. He shouted at them:

“Brothers, brothers!”

They asked him: “Who are you and what do you want?”

“You must tell the elder whom you are going to meet not to forget what I had asked him to do”.

The brothers found the elder, saluted him and falling on their knees they were asking him for some advice which would help them towards their salvation. Indeed, he taught them and they benefited a great deal. They also told him about the man they had seen while they had been on their way to the cave and about his request.

The elder knew for whom they were talking about but pretended he didn’t have a clue. Instead he said: “No other man lives here”. However, the brothers who were continuously bowing in front of him and grasping his legs, made him reveal who it was that they had seen.

The elder lifting them up, said to them: “Only if you give me your word that you will not talk about me as if I am a saint to anyone until I depart for my Lord, I will explain the situation”. They did as he had asked them to and he said:

“The man whom you have seen dressed in white is the Lord’s angel who came to poor little me and said: ‘Please beg the Lord on my behalf so that I may return to my place because the time designated by the Lord has come’. When I asked him what the reason for his penance was, he said: ‘It happened that in a regional town many people had been making the Lord angry with their sins for a long time. He sent me to punish them mercifully. However, when I saw how corrupt they had been, I imposed a heavier penance so that many of them perished. That is the reason why I was sent away from the face of my Lord, Who was the One to authorize this mission’. When I said to him: who am I to intercede to the Lord for an angel, he said: ‘If I didn’t know that the Lord accepts the prayers of his honest servants I would not be coming here to pester you’.

At that very moment I was astonished at the infinite mercy of the Lord and his infinite love for man. He made him worthy of talking to Him and seeing Him. He also designated His angels to serve men and be in contact with them, just like it happened with the blessed servants Zachariah and Kornelios and Prophet Elijah and other saints. I felt admiration with all these and thanked Him for his mercy”.

Shortly after this incident, our blessed father passed away. The brotherhood buried him with honor, chanting hymns and prayers. Let us try to imitate this hermit’s virtues with the power of our Lord Jesus Christ, Who wants everyone to be saved and acknowledge His truth.

From the ‘Large Gerontiko’

Όταν πάει κανείς με τον διάβολο… (Γέροντας Παΐσιος Αγιορείτης)

Όταν πάει κανείς με τον διάβολο, με πονηριές, δεν ευλογεί ο Θεός τα έργα του.

Όταν πάει κανείς με τον διάβολο, με πονηριές, δεν ευλογεί ο Θεός τα έργα του. Ό,τι κάνουν οι άνθρωποι με πονηριά, δεν ευδοκιμεί.

Μπορεί να φαίνεται ότι προχωράει, αλλά τελικά θα σωριάσει.

Το κυριότερο είναι να ξεκινά κανείς από την ευλογία του Θεού για ό,τι κάνει!

Ο άνθρωπος, όταν είναι δίκαιος, έχει τον Θεό με το μέρος του.

Και όταν έχει και λίγη παρρησία στον Θεό, τότε θαύματα γίνονται.

Όταν κανείς βαδίζει με το Ευαγγέλιο, δικαιούται την θεία βοήθεια.

Γέροντας Παΐσιος

Τhe Goodness of God

Beloved, follow not that which is evil, but that which is good. He that doeth good is of God: but he that doeth evil hath not seen God (3John 1:11).

One of the most common affirmations in Orthodox services is the goodness of God. Many services conclude with the blessing: “For He is a good God and loves mankind.” The goodness of God is utterly foundational to our faith – and yet that goodness is itself a mystery: it is not always apparent and remains a conundrum to those who are outside of the faith.The so-called “problem of evil” with which non-believers frequently assault belief in the existence of a good God points to the problematic character of goodness.

God is good – but not in a way that is obvious. The goodness of God can be known – as God can be known. Neither, however, are readily apparent.

In some of the early patristic writings, particularly those that can be described as “apophatic” (“unable to be spoken”) God is not only affirmed as good but as “hyper-good,” that is, His goodness is beyond anything we know – it is a transcendent goodness. The God made known in the Incarnation of Christ is indeed “unknowable.” It is the Incarnation of Christ that has made Him known.

No one has seen God at any time. The only begotten Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, He has declared Him (John 1:18)

All things have been delivered to Me by My Father, and no one knows the Son except the Father. Nor does anyone know the Father except the Son, and the one to whom the Son wills to reveal Him (Matt. 11:27).

We come to know the attributes of God in the same manner. The goodness of God is the goodness we see in the Incarnation of Christ; the power of God is the power we see in Christ; the kindness of God is the kindness we see in Christ; the love of God is precisely revealed in Christ.

St. Paul writes of the “attributes” of God being clearly seen through the things He created – but the passage is not necessarily the grounds for a “natural” theology (a knowledge of God derived from contemplating nature).

For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who suppress the truth in unrighteousness, because what may be known of God is manifest in them, for God has shown it to them. For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead, so that they are without excuse, because, although they knew God, they did not glorify Him as God, nor were thankful, but became futile in their thoughts, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Professing to be wise, they became fools, and changed the glory of the incorruptible God into an image made like corruptible man—and birds and four-footed animals and creeping things. (Romans 1:18-23).

St. Paul, I believe, is here describing the “fall” of man and man’s ignorance of God which it brought. The passage is consistently placed in the past tense. “Although they knew God,” etc. This is much different than saying that “knowing God” they are not thankful, etc. Instead he describes the long history of mankind before Christ as people who have become “futile” in their thoughts, and having their “foolish hearts darkened.”

However, it does seem to suggest that this knowledge can be restored as our hearts are enlightened – which is an inherent part of our living communion with Christ. But this knowledge is one that is seen only through an enlightened heart, again made possible only in the Incarnation of Christ

It is important to approach the mystery of goodness in such a manner. The goodness of God is a goodness made known in Christ and not an intellectual category or philosophical concept that can be described apart from Christ. Such a separate concept is the secularization of goodness – ultimately a blasphemous approach (“There is none good but One, that is, God” – Luke 18:19).

The mystery of God’s goodness is most especially to be found in the mystery of the Cross. In the gospels Christ is described as “going about doing good” as well as healing the diseases of people. But the depth of that mystery is found in His death and resurrection.

The mystery of the Cross is the triumph of foolishness over man-made wisdom; the triumph of weakness of man’s perceived power; the ultimate victory of good over evil. The most common image of the death and resurrection of Christ in the Eastern Church is the icon of Christ’s Descent into Hell – for it is this icon that carries the fullest expression of the theological content and reality of His death and resurrection. It not only depicts his victory over death and evil (shown as the devil bound in chains), but also show the cosmic and timeless element of His victory as He grasps the hands of Adam and Eve to lead them out of the bondage of sin and death.

The Christian definition of good is the goodness of God. In the world in which we live we do not see that goodness in abstraction but in the fullness of its conflict with evil and its ultimate triumph. The Gospel presumes and acknowledges the presence of evil while at the same time affirming that goodness, in Christ, overcomes that evil.

In the classical teaching of the Fathers, evil is not a something, a force or a presence: it is an action driven by a distorted will. It is an opposition to God, but without meaning or substance except as an opposition. Evil is thus not a presence, but a tragic movement towards absence. It is not communion with God but a self-ward movement towards non-being.

The great struggle within our world, as presently constituted, is not between ourselves and the forces of a blind and rudderless nature, but a struggle with the consequences of that relentless challenge. The Cross is not an image that excludes the brutal forces of wicked powers – it is the triumph of love and forgiveness in the very heart of those struggles.

Goodness cannot be abstracted from the human tragedy – it is known and experienced within the very context of that tragedy in the fullness of the Cross of Christ. This is a radical departure from the philosophical discussion of the problem of evil. Christianity is not a set of ideas that compete on the playing field of philosophical systems. It is event and relationship neither imaginary nor abstract. This occasionally leaves classical Christianity at a disadvantage – unwilling to grant the givens of an alien philosophy – and thus seeming silent or weak in the face of a serious intellectual challenge. But Christianity is a language that is spoken in the tongue of the Logos, whose incarnation, death and resurrection speak with the eloquence of the true and living God.

St. Paul recognized that his preaching of the Cross of Christ would either make him seem weak or foolish. It is a weakness and a foolishness that modern Christians should not disdain. For the weakness of God is stronger than death. The foolishness of God is wiser than all men.

So Your Child Wants to be a Monastic?

The following talk (slightly condensed) was given [in 1984] at the Saint Herman Winter Pilgrimage in Redding, California.

I should like to ask you to think of something you may not have considered before, How would you feel if your son or daughter expressed the desire to enter a monastery? You may be Orthodox, and very devout; you may he diligent in attending services and reading spiritual books; you may have tried your best to raise your children in an Orthodox manner; you may even admire monasticism. Nonetheless, how would you really feel?

We live in a time and society quite different from Greece and Holy Russia, where monasticism was a visible and acceptable part of life. It was not uncommon for entire families to make pilgrimages to monasteries. Few people today, however, have any significant exposure to monasticism and it is little wonder that in our un-Orthodox and even anti-Christian society, the very thought of one’s child becoming a monastic can seem very threatening.

There are a number of reasons one can give for such a reaction. Lack of familiarity breeds fear. Not a few people imagine monasticism to be very grim and even inhuman. They may envision their child locked behind a grating and subsisting for the rest of his or her life on bread and water. The other extreme is an equally- erroneous view of a romanticized spiritual state in which the child spends his days floating above the ground in an exalted state of endless holiness. In both cases it is imagined that entering a monastery presupposes leaving behind the human race. The reality of the monastic life is a far cry from either of these extremes. Your son or daughter—who is always late, leaves socks and soda bottles everywhere and is generally infuriating–will not turn into an instant anchorite. Anyone who leaves the world for the monastery brings all of his weaknesses and defects with him. He may learn to overcome some of them; others he will have until bodies, In any case, if your child becomes a monastic, he or she will not be living without human warmth and human relationships, and in spite of everything, you will still recognize them as being one of your own progeny.

Whatever your initial reaction to the issue of monasticism and your child, it depends to a great extent on how you as a parent view the Orthodox family and your position as an Orthodox individual in the contemporary secular world. Surrounded as we are by worldly standards and a materialist culture, we forget that Christ calls all of His followers to separate themselves from the world: Be not of this world. This is the trumpet call of monasticism. With this understanding, you should be more ready to peacefully acquiesce to the son or daughter who has found it in his heart to answer this call by taking upon himself the monastic yoke.

We are, however, the unfortunate products of our fallen nature, and it is rare that even a pious Orthodox parent is thrilled to hear that their offspring desires to enter a monastery. More often there arise some very strong reactions in the heart which, however innocent and well-intentioned, are nonetheless aspects of our fallen emotional and psychological nature – and a sad reflection of our un-Orthodox background and environment. With this in mind we can examine some of the emotional responses which this issue so often evokes.

Verbally, the various emotions stem from the pivotal question, “Why?” Why does anyone leave the world to enter a monastery? If the reason is legitimate, it is because in spite of all his failings and weaknesses, your child loves God more than anyone or anything in the world–more than the life you helped shape him for, more than his automobile, more than the school to which you were going to send him, more than his family… And here the very natural feeling of jealousy arises. As parents you may endeavor to replace God as being central in your child’s affections and persuade him to forsake monasticism, If you succeed, you will only make the child unhappy, and if you fail, you’ re going to feel very hurt.

Secondly. you may feel estranged or shut out from your child’s life. If your daughter goes to a monastery, and it’s a life you have not shared, you may feel you can’t relate to her. If she married, even if she moved a thousand miles away, you would very likely feel that you were still more a part of her life than if she became a nun and lived 50 miles away. A married daughter would still need advice on how to cope with the children’ s illnesses or how to manage a tight budget. On the other hand, if she were in a convent, you could hardly give her advice on how to do Matins, and even if you are Orthodox, you might feel emotionally adrift and very awkward with this suddenly foreign someone in black whose life is so different from your own. Then there is also the fact that most parents look forward to being grandparents, this is a big issue, especially with mothers.

You may feel threatened. You spend your whole life nurturing the well-being of your children: you feed them and worry over them; you help them to discover their abilities and you encourage them to develop their talents. Perhaps your son is a natural musician or your daughter a born lawyer, and you spend your life supporting them–emotionally and financially–and preparing them to be successful in the world. And after all these years of effort and anxiety, they suddenly decide they want no part of it, they don’t want the world, nor the life that you envisioned for them. This can be a very threatening and painful revelation. Very often parents feel that in rejecting the world, their child is also rejecting them. This is not necessarily true at all, but this feeling sparks most of the disputes between parents and their children over the issue of monasticism. Here also parents may feel they have failed in some way in their raising of the child, that he or she should choose such an “aberrant” path in life. This is also a painful thought.

The rather heated emotions which may arise over the issue of monasticism and one’s child frequently result in a barrage of reproaches. The following examples are not in the least hypothetical; they come from a list of actual remarks made by real mothers and fathers, some of whom consider themselves to be devout Orthodox. Their responses illumine the essence of the dispute as it is felt in the heart of those who are Orthodox and yet live in the world. They’ve said that we are not taking responsibility for ourselves; that we are just leaning on someone else so as to avoid having to make our own decisions. They say that if we love our neighbor we should be working to improve society and not dropping out of it into some euphoric dream. We often hear that monasticism is mere ostentation, some kind of fake spirituality: “Why don’t you stick it out in the world like the rest of us, where you have to deal with real life and real problems?” They say monasticism is selfish, egocentric, it divides and ruins the family; monasticism is “financially unstable”: What about your future security? Why don’t you just get a good job and send them all the money?…

While these remarks are quite varied, there is a common denominator, and that is worldliness. They are all rooted in a very worldly orientation. It is the complete and absolute rejection of this perspective on the part of the monastic aspirant which often makes the dispute between parents and child so violent, Although perhaps unconscious, the parents’ message underlying all this is: Conform yourself to the world; fit in; get a secure job; settle down; do what everyone else does…; spirituality is fine, but there’s no need to be extreme. We have already seen, however, that Christianity is otherworldly; by its very notate it is extreme: if you lose your life you shall gain it; if you try to hang onto it you will lose it; God became man that men might become gods. What could be more extreme?

Seek ye first the kingdom of God

Orthodoxy is the means by which we ascend unto God, through surrendering our own ego and self-will. Orthodoxy means war–against one’s fallen nature, against the devil, and against the world. This applies to all Orthodox Christians. Even those who live in the world–who have children and hold jobs–are required to keep themselves in some sense apart from the world. And there can be no compromise. The world is not and cannot be our home, and whether we choose to marry Christ or an earthly spouse, we can in no sense marry’ the world. We see, however, that it is precisely this desire–to have both God and the world–that is at the rooter the conflict evoked by the child’s entrance into monasticism. Experiencing their own reaction to the child’s rejection of the world may make the parents realize, perhaps as never before, their own attachment to the world, and how unwilling they are to sever themselves from the values and desires of the anti-Christian society in which they live.

It is especially difficult to struggle against the accepted view of the family which in this country has received a pseudo-religious status; youngsters are often all but worshipped as gods by their parents who see them as fulfilling their own egos. This is not Orthodox; it is, in fact, very destructive of our Orthodoxy which teaches that children are not the possession of their mothers and fathers: they are not playthings of their parents’ imaginations. Children are given by God for a time that they may be raised up in the knowledge of Him, and after that He summons them as He will. The duty of parents is not to prepare children to settle comfortably in the world, but to shepherd their souls, to prepare them to battle against the fallen world. Those who choose to fight in the front lines are those who hear the monastic calling. If your child wants to enlist in that war, he will swear before God and man that despite his sinfulness and frailties that overwhelm him at every hour of the day, he cannot find rest apart from God.

If such is the inclination of your child, do not hold him back, however logical your reasons For wanting to do so may be. If the desire for monasticism is simply a fanciful notion, they will find out soon enough, and nothing will be harmed by their trying. If, however, such a desire has indeed been planted by God as a means of their achieving salvation, don’t thwart it by trying to persuade him first to finish school or experience life in the world. Bring to mind the countless number of monastics, both men and women, whose spiritual legacy has so greatly enriched our holy Orthodox Church. If your child has the desire and determination to follow in their steps, however weakly, bless him, let him go. And may this blessing be also unto your own salvation and that of others.

Το Θανατο του παιδιου ( Γεροντας Παϊσιος )

- Μια μάνα, Γέροντα, που το παιδί της πέθανε πριν από εννέα χρόνια, σας παρακαλεί να

κάνετε προσευχή να το δη έστω στον ύπνο της, για να παρηγορηθή.

- Πόσων χρόνων ήταν το παιδί; ήταν μικρό; Είναι σημαντικό αυτό. Άμα το παιδί ήταν

μικρό και η μητέρα είναι σε κατάσταση που, αν της παρουσιασθή, δεν θα αναστατωθή, θα

παρουσιασθή. Αιτία είναι η μητέρα που δεν παρουσιάζεται το παιδί.

- Μπορεί, Γέροντα, αντί να παρουσιασθή το παιδί στην μητέρα που το ζητάει, να

παρουσιασθή σε κάποιον άλλον;

- Πως δεν μπορεί! Κανονίζει ανάλογα ο Θεός. Όταν ακούω για τον θάνατο κάποιου νέου,

λυπάμαι, αλλά λυπάμαι ανθρωπίνως. Γιατί, αν εξετάσουμε τα πράγματα πιο βαθιά, θα δούμε ότι, όσο μεγαλώνει κανείς, και περισσότερο αγώνα πρέπει να κάνη, αλλά και περισσότερες αμαρτίες προσθέτει. Ιδίως όταν είναι κοσμικός, όσο περνούν τα χρόνια, αντί να βελτιώση την πνευματική του κατάσταση, την χειροτερεύει με τις μέριμνες, με τις αδικίες κ.λπ. Γι' αυτό είναι πιο κερδισμένος, όταν τον παίρνη ο Θεός νέο.

-Γέροντα, γιατί ο Θεός επιτρέπει να πεθαίνουν τόσοι νέοι άνθρωποι;

- Κανείς δεν έχει κάνει συμφωνία με τον Θεό πότε θα πεθάνη. Ο Θεός τον κάθε άνθρωπο

τον παίρνει στην καλύτερη στιγμή της ζωής του, με έναν ειδικό τρόπο, για να δώση την ψυχή

του. Εάν δη ότι κάποιος θα γίνη καλύτερος, τον αφήνει να ζήση. Εάν δη όμως ότι θα γίνη

χειρότερος, τον παίρνει, για να τον σώση.

Μερικούς πάλι που έχουν αμαρτωλή ζωή, αλλά έχουν

την διάθεση να κάνουν καλό, τους παίρνει κοντά Του, πριν προλάβουν να το κάνουν, επειδή

ξέρει ότι θα έκαναν το καλό, μόλις τους δινόταν η ευκαιρία. Είναι δηλαδή σαν να τους λέη:

«Μην κουράζεσθε· αρκεί η καλή διάθεση που έχετε». Άλλον, επειδή είναι πολύ καλός, τον

διαλέγει και τον παίρνει κοντά Του, γιατί ο Παράδεισος χρειάζεται μπουμπούκια.

Φυσικά οι γονείς και οι συγγενείς είναι λίγο δύσκολο να το καταλάβουν αυτό. Βλέπεις,

πεθαίνει ένα παιδάκι, το παίρνει αγγελούδι ο Χριστός, και κλαίνε και οδύρονται οι γονείς, ενώ

έπρεπε να χαίρωνται, γιατί που ξέρουν τι θα γινόταν, αν μεγάλωνε; Θα μπορούσε άραγε να

σωθή;

Όταν του 1924 φεύγαμε από την Μικρά Ασία με το καράβι, για να έρθουμε στην Ελλάδα,

εγώ ήμουν βρέφος. Το καράβι ήταν γεμάτο πρόσφυγες και, όπως με είχε η μητέρα μου μέσα στις φασκιές, ένας ναύτης πάτησε επάνω μου. Η μάνα μου νόμισε ότι πέθανα και άρχισε να κλαίη.

Μια συγχωριανή μας άνοιξε τις φασκιές και διαπίστωσε ότι δεν είχα πάθει τίποτε. Αν πέθαινα

τότε, σίγουρα θα πήγαινα στον Παράδεισο. Τώρα που είμαι τόσων χρονών και έχω κάνει τόση

άσκηση, δεν είμαι σίγουρος αν πάω στον Παράδεισο.

Αλλά και τους γονείς βοηθάει ο θάνατος των παιδιών. Πρέπει να ξέρουν ότι από εκείνη

την στιγμή έχουν έναν πρεσβευτή στον Παράδεισο. Όταν πεθάνουν, θα 'ρθούν τα παιδιά τους με εξαπτέρυγα στην πόρτα του Παραδείσου να υποδεχθούν την ψυχή τους.

Δεν είναι μικρό πράγμα αυτό!

Στα παιδάκια πάλι που ταλαιπωρήθηκαν εδώ από αρρώστιες ή από κάποια αναπηρία ο

Χριστός θα πη: «Ελάτε στον Παράδεισο και διαλέξτε το καλύτερο μέρος». Και τότε εκείνα θα

Του πουν: «Ωραία είναι εδώ, Χριστέ μας, αλλά θέλουμε και την μανούλα μας κοντά μας». Και ο Χριστός θα τα ακούση και θα σώση με κάποιον τρόπο και την μητέρα.

Βέβαια δεν πρέπει να φθάνουν οι μητέρες και στο άλλο άκρο. Μερικές μανάδες

πιστεύουν ότι το παιδί τους που πέθανε αγίασε και πέφτουν σε πλάνη.

Μια μητέρα ήθελε να μου δώση κάτι από τον γιο της που είχε πεθάνει, για ευλογία, γιατί πίστευε ότι αγίασε. «Έχει ευλογία, με ρώτησε, να δίνω τα πράγματά του;» «Όχι, της είπα, καλύτερα να μη δίνης». Μια

άλλη είχε κολλήσει την Μεγάλη Πέμπτη το βράδυ στον Εσταυρωμένο την φωτογραφία του

παιδιού της που το είχαν σκοτώσει οι Γερμανοί και έλεγε: «Και το παιδί μου σαν τον

Χριστό έπαθε». Οι γυναίκες που κάθονταν και ξενυχτούσαν στον Εσταυρωμένο την άφησαν, για να μην την πληγώσουν. Τι να έλεγαν; Πληγωμένη ήταν.

Γεροντας Παϊσιος

Να συγκρίνουμε την δοκιμασία μας με την δοκιμασία του άλλου. ( Γεροντας Παϊσιος )

Να συγκρίνουμε την δοκιμασία μας με την μεγαλύτερη δοκιμασία του άλλου. Το καλύτερο φάρμακο για την κάθε δοκιμασία μας είναι η μεγαλύτερη δοκιμασία των συνανθρώπων μας, αρκεί να την συγκρίνουμε με την δική μας δοκιμασία, για να διακρίνουμε την μεγάλη διαφορά και την μεγάλη αγάπη που μας έδειξε ο Θεός και επέτρεψε μικρή δοκιμασίασ' εμάς.

Τότε θα Τον ευχαριστήσουμε, θα πονέσουμε για τον άλλον που υποφέρει πιο πολύ καιθα κάνουμε καρδιακή προσευχή να τον βοηθήση ο Θεός. Μου έκοψαν λ.χ. το ένα πόδι: «Δόξα Σοι ο Θεός, να πω, που έχω τουλάχιστον ένα πόδι· του άλλου του έκοψαν και τα δύο».

Και αν

ακόμη μείνω ένα κούτσουρο, χωρίς χέρια και πόδια, πάλι να πω: «Δόξα Σοι ο Θεός, που περπατούσα τόσα χρόνια, ενώ άλλοι γεννήθηκαν παράλυτοι».

Εγώ, από την στιγμή που άκουσα ότι ένας οικογενειάρχης έχει έντεκα χρόνια αιμορραγία, είπα: «Τι κάνω εγώ; Κοσμικός άνθρωπος αυτός και να έχη έντεκα χρόνια αιμορραγία, να έχη παιδιά, να πρέπη να σηκωθή το πρωί να πάη στην δουλειά, και εγώ ούτε επτά χρόνια δεν συμπλήρωσα που έχω αιμορραγίες!».

Αν σκέφτωμαι τον άλλον που υποφέρει τόσο πολύ, δεν μπορώ να δικαιολογήσω τον εαυτό μου. Ενώ, αν σκέφτωμαι ότι εγώ υποφέρω και οι άλλοι είναι μια χαρά, ότι σηκώνομαι την νύχτα κάθε μισή ώρα, επειδή έχω πρόβλημα με το έντερο και δεν μπορώ να κοιμηθώ, ενώ οι άλλοι κοιμούνται ήσυχα, δικαιολογώ τον εαυτό

μου, αν γογγύσω. Εσύ, αδελφή, πόσον καιρό έχεις τον έρπητα;

- Οκτώ μήνες, Γέροντα.

- Βλέπεις; Ο Θεός σε άλλους τον αφήνει δύο μήνες, σε άλλους δέκα μήνες, σε άλλους δεκαπέντε. Καταλαβαίνω, είναι μεγάλος ο πόνος. Μερικοί φθάνουν σε απόγνωση.

Ένας κοσμικός όμως που έχει έρπητα έναν-δύο μήνες και από τον πολύ πόνο απελπίζεται, να μάθη ότι ένας πνευματικός άνθρωπος τον έχει έναν χρόνο και κάνει υπομονή και δεν γογγύζει, τότε αμέσως παρηγοριέται. «Βρε, λέει, εγώ τον έχω δύο μήνες και έφθασα στην απελπισία· ο άλλος ο καημένος έναν χρόνο τον έχει και δεν μιλάει!

Εγώ κάνω και αταξίες, ενώ εκείνος ζη πνευματικά!». Οπότε βοηθιέται χωρίς συμβουλή!

π. Παισιος

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)