Μετά από προσεκτική επιτόπια έρευνα και μακρόχρονη εξέταση που πραγματοποίησα σε εκατοντάδες παλαιότερες και νεότερες τοιχογραφίες και φορητές εικόνες στον ευρύτερο ελληνικό χώρο, τις όμορες χώρες Βουλγαρία, Σερβία και Τουρκία και ακόμη στη Ρωσία και την Παλαιστίνη και αφού μελέτησα με προσοχή τόσο το πνεύμα όσο και τις κυριότερες εκφράσεις και οραματισμούς της σύγχρονης εικονογραφίας, διέκρινα τέσσερις κατευθύνσεις των εικονογράφων, στις όποιες σύγχρονοι και παλαιότεροι καλλιτέχνες έχουν ενσαρκώσει την τέχνη τους και έχουν σηματοδοτήσει τούς οραματισμούς τους.

Η πρώτη χρονολογικά είναι η παλαιότερη και χαρακτηρίζεται για την αντιγραφή κατευθείαν δυτικών προτύπων τα όποια πολλές φορές απλοποίησαν ή παραποίησαν οι εικονογράφοι με αποτέλεσμα η τέχνη τους αυτή να είναι ανθρωποκεντρική τέχνη που επικράτησε, όπως είναι γνωστό, στη Δύση με την Αναγέννηση και την κυριαρχία τού Αριστοτέλη και των ανθρωπιστικών σπουδών(humanismus). Έτσι εικόνες του Χριστού, της Θεοτόκου, του Ευαγγελισμού, της Γεννήσεως τού Χριστού, της Μεταμορφώσεως, της Προσευχής στη Γεσθημανή, του Νυμφίου, της Σταυρώσεως, της Αποκαθηλώσεως, του Μυστικού Δείπνου, της Αναστάσεως, της Πορείας προς Εμμαούς, της Αναλήψεως κ.α. ανακαλούν στη σκέψη μας έργα των Ραφαήλ, Bοtticeli, Τισιάνου, Leonardo ba Vinci, Credi, Lippi, Ribera, Cigoli, Donatello, Greco, Corn, Cort, Rembrandt, Bellini, και άλλες, πού είναι από πλευράς τέχνης έργα σημαντικά, είναι όμως ξένα και άσχετα προς το ύφος, το πνεύμα και το βαθύ νόημα της Ορθοδοξίας.

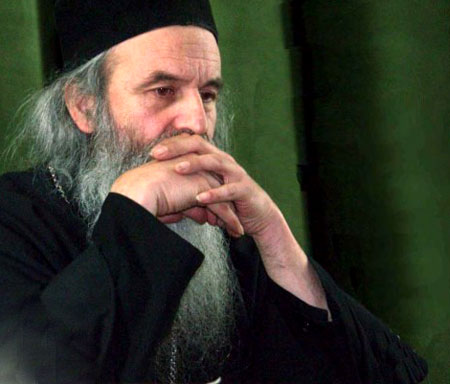

Ο απόστολος Πέτρος από τη Μεταμόρφωση (λεπτομέρεια) Τοιχογραφίες Καθολικού Μονής Βατοπαιδίου (1312)

Η δεύτερη κατεύθυνση χαρακτηρίζεται από μια προσπάθεια επιδιόρθωσης τάχα των παλαιών προτύπων της βυζαντινής εικονογραφίας ή δημιουργίας νέων βάσει των μεθόδων της ευρωπαϊκής τέχνης. Γνήσια δηλ. αγιογραφικά έργα μεταποιούνται από το φυσικότερο (ωραιομορφία, ανατομή, σχέδιο, προοπτική κ.α.), για να ικανοποιηθούν απλά και μόνο οι αισθητικές αντιλήψεις των συγχρόνων. Τέτοια συνήθως «διορθωμένα» έργα είναι φορητές εικόνες τέμπλου, η Πλατυτέρα, ο Παντοκράτορας του τρούλου, οι τέσσερις Ευαγγελιστές, το Δωδεκάορτο, εικόνες εορταζομένων αγίων κ.ά. Κυριότεροι εκπρόσωποι αυτής της κατεύθυνσης είναι ο L Thirsch,, που πραγματοποίησε τις τοιχογραφίες της Ρωσικής Εκκλησίας στην Αθήνα, ο L. Seit, που ζωγράφισε τις εικόνες του τέμπλου της Μητροπόλεως Αθηνών, ο Σ. Χατζηγιαννόπουλος, που εργάστηκε στο ναό της Αγίας Ειρήνης της Χρυσοσπηλιώτισσας, ο Κ. Φανέλλης, που επιχείρησε να διακοσμήσει το ναό της Μητροπόλεως, τον Άγιο Ελευθέριο κ.α.

Η τρίτη κατεύθυνση χαρακτηρίζεται από την επάνοδο στις μέρες μας στα πρόσωπα της Ορθόδοξης εικονογραφικής Παράδοσης, γεγονός που οφείλεται στη μελέτη και σπουδή της βυζαντινής εικονογραφίας, σε ημεδαπά και διεθνή βυζαντινολογικά συνέδρια, τα οποία μελετούν, παρουσιάζουν και εκθέτουν την αξία και τη σημασία της, προβάλλοντας συγχρόνως τα προβλήματά της. Παράλληλα πραγματοποιούνται όχι μόνο ειδικές εκθέσεις βυζαντινών φορητών εικόνων και τοιχογραφιών στον ευρύτερο ελληνικό χώρο και σε χώρες τού εξωτερικού, αλλά γίνονται και ειδικές έρευνες συντήρησης και αποκατάστασης μνημείων και συνόλων, γεγονός που αποσπά το θαυμασμό των αναπτυγμένων θεολογικών και καλλιτεχνικών κύκλων σ’ ολόκληρο τον κόσμο. Πολλοί εξάλλου συντηρητές έργων τέχνης και αρχαιοτήτων ειδικεύτηκαν στην εικόνα και την τοιχογραφία, καθάρισαν, στερέωσαν και συντήρησαν χιλιάδες φορητές κυρίως εικόνες και τοιχογραφίες και αποκάλυψαν τον πλούτο κυρίως της βυζαντινής και μεταβυζαντινής αγιογραφίας και τέχνης.

Έτσι φωτισμένοι εικονογράφοι πού κατανόησαν τη σημασία της Παράδοσης στράφηκαν με ζήλο και σεβασμό στα γνήσια βυζαντινά ορθόδοξα ζωγραφικά πρότυπα, δημιουργώντας θαυμαστά πράγματι έργα με βάση τα παλαιότερα πρότυπα της ορθόδοξης ζωγραφικής τέχνης. Ως παράδειγμα αυτής της μεταστροφής και της αναζήτησης θα μπορούσα να αναφέρω αρχικά τον Αγιορείτη Μοναχό Μελέτιο Συκιώτη, που δημιούργησε εξαίρετα πιστά αντίγραφα από το ναό τού Πρωτάτου των Καρυών του Αγίου Όρους (Μακεδονική Σχολή), τον Φώτη Κόντογλου, που δίδαξε και έγραψε για τη βυζαντινή έκφραση της εικόνας, τούς αδελφούς Ιωασαφαίους, Δανιλαίους και Παχωμαίους, που δημιούργησαν και δημιουργούν στο Άγιον Όρος χιλιάδες πιστά αντίγραφα τόσο της Κρητικής όσο και της Μακεδονικής Σχολής, όπως και δεκάδες άλλοι στη συνέχεια και εκατοντάδες αγιογράφοι μεταγενέστερα, που κατέβαλαν μεγάλες προσπάθειες δημιουργίας πιστών αντιγράφων της βυζαντινής εικόνας. Ταυτόχρονα αναπτυγμένοι κύκλοι μετακαλούν Έλληνες εικονογράφους στην Ευρώπη, την Αμερική, την Αυστραλία, την Αφρική, την Παλαιστίνη κ.α. για την εικονογράφηση ιερών ναών, ενώ χιλιάδες φορητές εικόνες εξαιρετικής βυζαντινής τέχνης πού δημιουργούνται καλύπτουν τις παρουσιαζόμενες ανάγκες.

Η τέταρτη κατεύθυνση της σύγχρονης εικονογραφίας εστιάζεται στην ελαφρά τροποποίηση παλαιών προτύπων και συγχρόνως στη με βήμα αργό αλλά σταθερό ανανέωση και οπωσδήποτε διεύρυνση των εκφράσεων και των προσανατολισμών της, όπου έγκειται ακριβώς ο πλούτος, το πνεύμα και το μεγαλείο της. Και η προσπάθεια αυτής της έκφρασης προϋποθέτει συνεχή καλλιτεχνική ορμή για εξωτερίκευση και επομένως ζώντα οργανισμό πού εκδηλώνεται αδιάκοπα και δεν επαναπαύεται σ’ εκείνο που πέτυχε. Σ’ αυτό ακριβώς το στοιχείο οφείλονται και οι γνωστές κατά περιόδους «αναγεννήσεις» και ο διαρκής πλουτισμός της βυζαντινής εικονογραφικής τέχνης στα χρόνια του Ιουστινιανού, των Μακεδόνων και Κομνηνών, των Παλαιολόγων και του 16ου αιώνα, που έδρασε η περίφημη Κρητική Σχολή αγιογραφίας με πρωτουργό τον Θεοφάνη τον Κρήτα. Και ναι μεν σήμερα οι προτιμήσεις των εικονογράφων στρέφονται στον παλαιολόγεια τέχνη και τα έργα της κρητικής αγιογραφίας, όμως δεν είναι αρκετές για μια πραγματική ανανέωση της βυζαντινής εικονογραφίας.

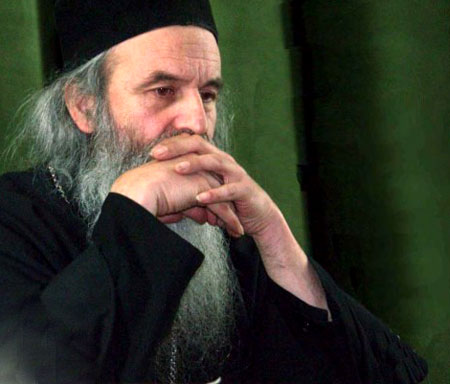

Η Δέηση στον νάρθηκα του παρεκκλησίου του Αγίου Δημητρίου στην Ιερά Μονή Βατοπαιδίου (επιζωγράφηση του 1791)

Γιατί αυτή η αναγέννηση δεν επιτυγχάνεται με τη μίμηση και δημιουργία των καλύτερων έστω παλαιολόγειων, λοιπών βυζαντινών και μεταβυζαντινών έργων της βυζαντινής ζωγραφικής, ούτε βέβαια με τα δύσκαμπτα σώματα της λαϊκοποιημένης εικονογραφίας της Τουρκοκρατίας, αλλά κυρίως με τη διεύρυνση, επέκταση και ακόμη τροποποίηση συνθέσεων στα πλαίσια του αληθινού νοήματος της βυζαντινής καθόλου αγιογραφίας και τέχνης. Η βυζαντινή δηλ. αγιογραφία παρέμεινε και είναι μία και μοναδική και κατά την ουσία και κατά το πνευματικό της περιεχόμενο, η μορφή της όμως δέχτηκε εξέλιξη. Άλλη ήταν ή μορφή της τέχνης των κατακομβών, άλλη επί Ιουστινιανού, άλλη επί Μακεδόνων, άλλη επί Παλαιολόγων και άλλη των μεταβυζαντινών χρόνων, επειδή ακριβώς η τέχνη αυτή δεν επιτρέπεται να αγνοεί το όλο πνευματικό κλίμα τού σύγχρονου ανθρώπου, όπως εξάλλου δεν αγνοεί τούτο και η ιθύνουσα Εκκλησία, η οποία συγχρονίζει το κήρυγμά της στις ανάγκες των χρόνων μας. Παραμένει όμως στην ουσία του το κήρυγμα χριστοκεντρικό, εμπλουτισμένο όμως με επιστημονικά και ψυχολογικά δεδομένα.

Από τα παραπάνω νομίζουμε έγινε φανερό πως η Βυζαντινή Τέχνη εκφράζει τον «σαρκωθέντα», τον «μεταμορφωθέντα», τον «ταπεινωθέντα», αλλά και τον θριαμβευτή Χριστό. Μέσα της κλείνει ένα μήνυμα πού είναι αποκλειστικά δικό της. Φυσικά δεν το καταλαβαίνουμε, αν δεν γνωρίσουμε τη σιωπηλή της γλώσσα, δηλ. τις γραμμές, τούς όγκους, τα χρώματα πού εκφράζουν τις σκέψεις και τα συναισθήματα ανθρώπων πού ανήκουν πια σ’ ένα μακρινό παρελθόν. Σε μας, πέρα από την άμεση ευχαρίστηση πού μας προσφέρει η θέα των αριστουργημάτων, μπορούμε να ανακαλύψουμε μέσα εκεί πολλούς θησαυρούς αρκετά πνευματικούς, με κορύφωμα τον πνευματικό της χαρακτήρα, που είναι ο χαράκτης της πορείας της με μοναδικό σκοπό να «φέρει χαμηλότερον» τον Θεό και να «ανεβάσει υψηλότερν» τον άνθρωπο.

http://www.pemptousia.gr/2014/11/i-tesseris-katefthinsis-tis-sigchronis-ikonografias/

Monasticism is like living something from the age that shall come, in which, as the Savior says: “They neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are as the Angels of God in heaven” (Matthew 22:30). We [monks] are not like the angels, yet life has a tendency towards that, and when you receive the call [to monasticism], you don’t know what hit you, because in this [human] nature you don’t have any confirmation. So then, of course, you need someone to validate or invalidate your call. Because if you don’t [do this], you will suddenly find – or you will start to think: I’ll go to madhouse with my calls!

Monasticism is like living something from the age that shall come, in which, as the Savior says: “They neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are as the Angels of God in heaven” (Matthew 22:30). We [monks] are not like the angels, yet life has a tendency towards that, and when you receive the call [to monasticism], you don’t know what hit you, because in this [human] nature you don’t have any confirmation. So then, of course, you need someone to validate or invalidate your call. Because if you don’t [do this], you will suddenly find – or you will start to think: I’ll go to madhouse with my calls!

So, the Spiritual Father can validate or invalidate this thing on some level, but even this level is quite difficult to be defined. The essential line is this: I’m the only one who knows if I am for monasticism or not. Nobody else [would]! And the Spiritual Father can validate or invalidate, but he can’t… Father Sophrony [Sakharov] had [in Paris] Fr. [Sergius] Bulgakov as Spiritual Father and when he confessed to him that he would like to go in Mount Athos to became a monk, his Spiritual Father replied to him with a French saying: “The best is the enemy of the good”. Father Sophrony considered this word of his Spiritual Father, but he didn’t accept it – finally he went to Mount Athos and became a monk.

I got you here to a very difficult matter, to a thinking in which we all must assume our responsibility before God, before eternity – and not only in patterns in which we entered, but yet in a spirit of responsibility and obedience. And I say again: monasticism exists only in the intimate dialogue of every soul with God our Creator. So, I am deeply touched by the love of that sister for her own monasticism and for you; she thinks if she was fulfilled [in monasticism], you will be fulfilled too. But if this [call] isn’t from God – not for her reasons (they have some value, but they’re relative) – the most important thing, the absolute thing is to find into God: is this my way, or not? And: are really the hardships I endure a sign that I’m not on the right path, or they are some obstacle that needs to be overcome – all of these, through prayer…

Question: What prayers do I need to make, for me to find out?

Fr. Raphael: Begin [to pray] with this question. Put it before God – any prayer. Ask Him: “O, Lord, how should I pray? What do You expect of me?” Any thought you have – just add to it “Lord!”; add to your thinking a bit of “Lord!”, add [Him] to all your thoughts. This way, if you add a bit of “Lord!”, instead of you thinking like an engine which runs for nothing, your thinking will become prayer, and the engine will start to move the wheels.

Question: Is it possible to have matrimony, and also holiness and Jesus’ Prayer?

Fr. Raphael: The holiness is the nature of the man, the one that we should acquire in this ephemerality, and it isn’t something special for man – I mean it’s something different from transient, for biological life. The holiness is the nature that’s eternal in God, so it’s the nature of man. And either in matrimony, either in monasticism, either in other ways – if they are – the man always seeks the holiness. But we transformed the sanctity into a pattern; we made from it a false image; we put the Saints onto a pedestal which is very high and distant from us, and we look at them with a reversed binocular, to make it even more distant – and afterwards we are wondering why we don’t get there.

Question: And how do we escape from these patterns?

Fr. Raphael: O, may Lord deliver you! You may have a little too much confidence in your youth. [You have to keep] always before your eyes the fact that God is a God of Love and, from there, [you have] to seek and to examine why [is happening] anything that hurts you…

I don’t like what I heard – Why? Because I’m a sinner, or because that word isn’t right.

And for the rest, I say again: May God guide you! The path [together] with God is the path of freedom. The freedom is, of course, dangerous – but I also got this image, when I was afraid to soar. I said to myself: But, if I won’t go… – let’s say we’re travelling to the Jerusalem above – if we won’t go on road because we’re afraid that something may happen to us on the way there, we’ll know only one thing for sure: we will remain here. If we’ll go, fine, maybe we won’t get there (which is not the case [when we are] together with God), but if we think [like] “Maybe we’ll get there, maybe we won’t get there”, we still have in our imagination 50% and 50%. If I stay, [if I remain], I have a 100% certitude I won’t get there!

I want, with all these, to give you a bit of courage. But with God, as long we stick to God, is impossible not to get there, as Christ said: “My sheep shall never perish, neither shall any one pluck them out of my hand” (John 10:28). And He added immediately: “My Father is greater than all; and no one is able to pluck them out of My Father’s hand” (John 10:29). I emphasize this “no one is able”! Yet man is gifted with such a great Divine freedom, that in my freedom I don’t have my Salvation guaranteed – God didn’t put me in a concrete box. I have a frightful freedom, but this doesn’t mean God can’t support me until the end. I can’t express myself here more concrete, more correct, less clumsy, because we are at some boundaries where the human reason isn’t applicable anymore. We have for the one side absolute certainty that we will get there, because Christ said “no one is able to pluck them”, and for the other side my freedom, which could separate me from God in any moment; but if I add “God forbid!”, I can’t get separated.

There is one more thing: when we begin to see Who is the God of Love, Who is also Almighty, you’ll begin to see that you can’t get lost with this God – it’s impossible! [It is] when you see that our fallen nature is so evil, that everything God does for our Salvation we undo for our perdition, [that] you can’t save yourself in no way. We live, as a Serbian woman said many years ago, [thinking]: “I am tormented in Orthodoxy by this incertitude: that I may be saved, or I may be not. I would rather be like Protestants, who are sure that they are already saved!”

But something in her words “scratched” me and, after some time, I realized that we Orthodox aren’t living in incertitude, but into a double certitude. As I see myself, it’s impossible to save myself. Look, Christ spilled His blood for the Hebrew people and for the entire world, and the Jews called “His blood [to be] on us and on our children” (Matthew 27:25) as a curse. So, how can be saved such a man, even with the almighty love of God? And yet, when you see that God Christ, with divine power, divine word, tried to put off that curse, saying to the women of Jerusalem: “Weep not for me, but weep for yourselves, and for your children” (Luke 23:28) – meaning “weep for those upon you called some minutes ago My blood, as a curse, and I spill it for Salvation.” [We have] such a God, Who even then doesn’t get offended!… And [Who], when they put nails through His hands, says: “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34); [Who], when He was dying by our hands, gives for our Salvation His body, broken by us; gives His blood, spilled by us – only if we want to. Well, with such a God, Who defeated even the Hell when He got there, making a path up to the staying to the right of Father – with such a God, how could you get lost?!

So, we have two certitudes: with me, salvation is totally impossible, and this is part of my confession. But, if I confess this, I also confess God – it is impossible to be lost with God. And, between these two impossibilities, I think God’s impossibility must triumph. It’s enough just to cling and stay, not to despair until the end because of enemy’s assaults – and [finally] God will drew me into his fishing net.

Question: How can we know if we have Grace after Liturgy?

Fr. Raphael: Notice one thing: when we are in Grace, we feel that everything is beautiful, that everything can’t have something else but a happy end. When we lose the Grace, we feel the darkness is so great, that we’ll never get out of it. Notice this is the characteristic of that condition. There is not and cannot be tragedy in God, however tragic our life may be. But those things of Hell and of falsehood are as any things of Hell – the work of falsehood wants us to despair. This is one thing, and I emphasize these effects for you to notice.

The second thing is we put very much emphasis on the preparation before Communion, for us to be, supposedly, worthy of commune. I say “supposedly” because we remain unworthy. Our worthiness is Christ. [Yet I see] we don’t understand well the need to find how to keep Communions’ Grace after Communion. In a way, this thing is more important than the preparation; this preparation before Communion is not for us to be worthy. This preparation is to prepare the soil of our soul. […] The most important thing is how to keep that Grace.

In this matter, I say to you, if you look to all the Philokalic Fathers, humbleness is the key. But what is humbleness? Because, beyond a certain pattern, we don’t know what humbleness is. For one thing, humbleness is spiritual realism. If I am the greatest sinner, then may God grant me the power to see I am the greatest sinner amongst people! This is a divine vision, that doesn’t belong to human reason, neither to comparison with the others. [Humbleness] belongs to a spiritual way of seeing things, a realist one. This is not a mannerism, but spiritual realism.

Secondly, Father Sophrony [Sakharov] defined humbleness as that quality of divine love which gives itself to the loved one without returning upon itself. This “without returning upon itself” means the humble one doesn’t consider upon himself, but seeks towards his loved one. Yet humbleness doesn’t mean just humiliation and carelessness for humiliation, but also care for the fulfillment of the loved one. Why? Because it lives through the loved one. It seeks into the loved one, it empties itself into the loved one, for it to receive in its emptied ego the loved one – for the loved one to rest into it, and for it to rest into the loved one. And that, in our [ecclesiastic] language, is called “perichoresis” – Father Sophrony used to called this “the pharmaceutical language of modern theology” [Fr. Raphael smiles], but [it is] a word which is the essence of eternal love.

On the other hand, I think a second definition will give you a better understanding of what we need to seek. Humbleness isn’t a thing by itself, it belongs to love. Father Sophrony said to me one day: “You think that what Saint Silouan said were great things, but know this: the only great thing is humbleness, because the pride prevents love.” Pride dwells in itself, and then, if I live in myself, neither of you will have place [here], nor God. But if I learn to empty myself, to give myself with the aim that God and whole humanity will have place [in me], then every person become a bearer of God and of the entire Universe. This is humbleness.

And then, [following] these paths, we’ll find both the justification to draw near the Holy Communion – [or] the worthiness, if you prefer, because the worthiness is not ours: then Christ will partake with us His worthiness. And, living in this spirit, we’ll be able to keep the Grace we receive in Communion.

Question: And, yet, how can we keep the Grace?…

Fr. Raphael: Well, by persisting on this path of humbleness. I mean, there are many things to say, but I say again – you will find your way through God, [together] with your Spiritual Father, each of you. The general path is the humbleness. Humbleness is the key to keep the Grace.

Question: And what if we don’t know what [humbleness] is, and we ask Lord to give us [humbleness]?

Fr. Raphael: [Then] Lord shall give it to you, so ask it from Lord – speaking of correct understanding…

Transcript from a conversation with youth of Association of Romanian Orthodox Christian Students, Bucharest, 14 March 2002

http://pemptousia.com/2014/11/humbleness-is-the-key-to-keep-the-grace/