A talk given in the New-Tikhvin women's Monastery, Ekaterinburg, Russia, October, 2011, during the visit of the Cincture of the Mother of God to Russia.

Your Eminence, eminent bishops, honorable fathers, dear Mother Abbess, brothers and sisters! It is a great joy for me to be in your monastery once again. As you know, this time we have arrived with the holy Cincture of the Mother of God. This is a very special holy shrine — very precious from the spiritual point of view. By God's providence we have brought the relic to this city in order to sanctify the city, and of course, for the sake of the monastics who live here. We know how pleasing the monastic life, and in general the existence of monasteries is to the Mother of God. We know how many times in the history of the Church the Mother of God appeared to chaste and pure souls and said, "There is my icon, take it and build a monastery." The Holy Mountain is the only existing monastic republic, dedicated entirely to her. The Most Pure Virgin is the Protectress of Mt. Athos. She herself told St. Peter the Athonite to go and live on the Holy Mountain, and said that he and his co-strugglers will be under her direct Protection. "I myself will be your Protectress, Healer, and Nourisher," she said. Appearing to St. Athansius the Athonite, she said the same thing she had said to St. Peter, adding, "I will be your Economissa (steward) and I will take care of all of you; but I want only one thing from you—that you keep your monastic vows." And to this day we, the Athonites, delight in her patronage and special intercession.

Therefore, my dear ones, it is a great blessing that we have come to monasticism. Our elder Joseph of Vatopedi of blessing repose very often said to us, "There is no greater blessing for a person than when God calls him to the monastic life. May the monk never, not even for a second, ever forget that God Himself called him." When we remember how we left the world, what went along with us then, we see that God's grace was upon us, that it accomplished our renunciation of the world, and led us to the monastery. Here we must fulfill three virtues in their entirety: non-acquisitiveness, obedience, and chastity. These virtues lead us in the spiritual life, root us in it, and help us attain the fullness of maturity in Christ.

Monasticism is the path of perfection, and therefore we monastics are called to acquire the fullness of grace. Not long ago, one monk came to me and said, "You know, I have no time to read." I said to him, "My child, the monastery is not a place of reading. You have come to the monastery not to read, and not even to pray. You have come to deny yourself and submit yourself to spiritual guidance. If you give yourself over in obedience to the abbot and not try to get as comfortable as possible in this life, then you will fulfill Christ's commandment exactly. He never said anything accidently, but always unmistakenly, and He said to us monks: Whoever will come after me, let him take up his cross and follow Me."

Whoever in the monastery fulfills his own desires and dreams is not denying himself. A monk should not have any dreams at all—no ambitions or plans. He comes as a man condemned to death, lifts his arms and says to the abbot, "Do with me as you will." By this he fulfills another of Christ's words: "He who wants to save his own soul will lose it." And if a monk understands the meaning of these words and places them at the foundation of his life, he will have a correct understanding of podvig, and all his problems will be solved. He becomes an organ of God's Providence and fully imitates our Lord Jesus Christ, Who, although sinless, came and stood on the level of us penitents, as if He also needed repentance. Christ did not just give commandments from the heavens for us to observe; He Himself came to us and demonstrated them to us in practice. And what did He say to us, absolutely clearly? "I have come not to do my own will, but the will of my Father Who sent Me." Our blessed elder Joseph told us in his talks, "What do you think, brothers: if Christ were to fulfill His own will—would that have been sinful? Nevertheless, He did not do that, so that He could be One Who first does, and then teaches." Man's will and desire is a brass wall. Not a clay, not a stone, not a cement, but a brass wall separating him from God. Blessed is the monk who obeys. Obedience is not a discipline; it is something different. Obedience is when you give over your heart. Monastic life is fully Christ-centered. Therefore the elder does not use his spiritual children's obedience for his own purposes. His task is to convince the monk to submit his will to the will of God.

If you have any questions, ask them and I will answer them if I can.

—How can one notice the appearance of a sinful thought, and cut off in time a passionate thought that infect us while it is still at the state of suggestion?

—Do not be over-preoccupied with thoughts—they need to be treated with disdain. One monk in our monastery once came to me and said, "I need to confess." I saw that he was carrying a notebook. I asked him, "What is that you have?" "It is my confession," he answered. "Well, give it to me," I said. "I will read your notebook." Just imagine—thirty pages of thoughts! I said to him, "Do you think you need to confess every thought that comes into your head? You'll end up in a psychiatric hospital that way!" He had written down even the thoughts that came to him during services. I told this brother, "Thoughts that come in do not mean anything." Even if the mind inclines toward them for a moment, this does not mean anything, absolutely nothing! Forget them! You need to confess only those thoughts that do not go away for a long time, that stay in the mind for days or weeks; but in general thoughts are soap bubbles.

I will tell you about yet another incident from life. One young man, a church-going man, fell into gluttony—he wanted to eat a shish kebob on a Wednesday, and went to buy it. He came to the store and the salesman said, "Forgive me but I just sold the last one." This young man then came to me and said, "This is what happened, and I would have eaten a shish kebob!" I said to him, "But you did not eat it? That is all! You gave in to a thought, but did not sin in deed." How is it with us? First there is the thought, and then it becomes a word, and then a deed. But a sin is considered committed when it becomes a deed. Therefore, be attentive and do not be preoccupied much with thoughts; disdain them. "For the thoughts of mortal men are miserable" (Wis. 9:14), literally, "Thoughts are cowardly"

—Fr. Ephraim, to what do you think monastics in Russia should be paying particular attention, so that our monasteries would be stronger and flourish?

—You need to pay attention to obedience. A monk should obey and not have passionate attachments; this especially relates to women monastics. I have one women's monastery, and when I go there, it all begins: "Geronda, pray for my aunt, my nephew, my nephew's neighbor. Geronda, pray for my brother, for my sister's friend." You shouldn't be concerned with your aunt's, your nephews' or their neighbors' needs. Pay attention to this, because the virtue of exile is particularly hard for women; they tend to be very attached to their relatives. They start praying fervently for them, but under the guise of prayer for their relatives, their hearts cleave to them again. Obedience, however, tells us to give ourselves wholly to Christ. Whoever does not renounce his property, says the Lord, cannot be my disciple. These are the words of Christ, Who was merciful, Who was a teacher of mercy! But do you remember what the man said after the Savior called him to follow Him? "Allow me to go and bury my father." He was not lying, after all; he would have done just that. But Christ said, "No let the dead bury their dead. You follow Me." Why do you think He said that? Because man's mind is called to illumination, and compared to this illumination, this sanctity, everything is insignificant, nothing. Or, for example, many people write letters to their relatives who are monks. The brothers ask me, "Geronda, should I answer the letter?" "No," I say, "you don't need to answer it. Pray for them, and that will be your greatest offering."

—How can a complicated and responsible monastic job having to do with monastery property management be combined with the commandment not to care for tomorrow?

—Whoever cares for these things is doing them in obedience—he has a "carefree care". St. Silhouan the Athonite was the steward, not even of the monks, but of the lay workers. At the same time he was a great man of silence, a true hesychast. Pay attention to this! Do you remember how he himself admitted in his recollections: "The abbot told me to be the steward of the workers, and I inwardly resisted. 'Oh, father, what are you burdening me with…'" He did not accept it right away only inwardly, and did not show swift obedience, although he went and did this job. But the level of his spiritual progress did not allow him the right to resist even inwardly. He himself admitted that for this resistance against the abbot he had headaches his whole life as a penance. So, be very careful. Look at how Christ mysteriously, in an amazing way equated the will of a lawful organ—that is, the abbot—with His own will. What does He say? "Whoever hears you hears Me, and whoever rejects you rejects Me." Therefore, another great saint of our times, Elder Porphyrius of Kavsokalyvia, emphasized the significance of joyful obedience.

—How can repentance be combined with spiritual joy, compunction and inner peace? Both are needed, but apparently contradict each other.

—To the extent that a person repents and has that inner lamentation commanded by Christ, he will feel simultaneously that this lamentation is joy-producing. Do not contemplate spiritual things by using the feelings or sentimentality. One may weep because he has a psychological problem, another weeps from sentimentality, while a third weeps for spiritual reasons. Unfortunately, we have not worthily responded to God's call—I am speaking of myself—and we do not measure up to God's grace and long-suffering for us. But we have known holy elders, our contemporaries, who had compassion for people and prayed for everyone with great pain of heart. They were always peaceful, joyful, and easy to be around. This is the wonder of a spiritual person.

—Do you think that the monastic virtues of the ancient fathers are possible in modern monasticism?

—Both monasticism and man have always been the same throughout all times. Of course, people of the twenty-first century unfortunately do not have the same self-mastery or strength as the ancients had. But if a person wants this, he can labor in asceticism according to his strength and experience the same grace as did the ancient fathers.

—How can we avoid depression when repenting? Where is the boundary between repentance and depression?

—In order to help us discern this, we have spiritual guides. One day a nun came to elder Porphyrius, who was clairvoyant. She had read much about remembrance of death and had begun to feel depressed from it, because it was beyond her strength. As soon as the elder saw this nun he could immediately see what the problem was. Before she even said anything, he said to her, "You do not have a blessing to exercise the remembrance of death. Think only about Christ's love." Thus, the podvig of repentance should be directed by a spiritual guide who looks at each person's spiritual state. When my elder, Joseph of Vatopedi, was young, he put much effort into self-criticism and began to get depressed because of it. Then our "grandfather", Joseph the Hesychast, said to him, "Son, work with this—but only a little, not too heavily." Of course, after maturing spiritually he had no problem with this practice.

It is because the spiritual state of the monk must be observed that the holy fathers prescribed that the spiritual father, the abbot, be always in the monastery. Of course, he can be absent for a few days, but in general he is continually with the brothers. Our laypeople, for example, see their spiritual father once or twice a month, the more reverent ones once a month; continual association with a spiritual father is not for them. But the holy fathers did institute this for monks because monks are as if walking a tightrope, and they need continual help.

—How can we discern salvific memory of death from ordinary fear of death, which even non-religious people feel?

—One person told me that he used to be very afraid of death. After he began coming to Mt. Athos, this fear disappeared completely. God gave him such a gift. Psychological fear is not a good fear; it rejects [death], but remembrance of death in Christ is victory over death.

Once a group of pilgrims came to our monastery, and after Compline I talked with them a little. I do not know why, but I began to talk with them about remembrance of death. There was one psychologist among them. He said to me later, "Father, we came to you on the Holy Mountain, and you began talking to us about such sad things." At first I did not understand what had happened. He then said, "Couldn't you have found something else to talk about? Why talk about death?" He was continually tapping his wooden armchair—a superstitious action against the evil eye. However, remembrance of death in Christ does not cause depression in people—it fills them with joy. After all, in Christ we conquer death, and pass over from death into life! We monks are the heralds of eternal life. Why? Because we already have a presentiment of the Kingdom of God in our hearts. Do you remember what Abba Isaiah said? "Remember the Kingdom of Heaven, and it will draw you in little-by-little." That is why a monk is always joyful. He already tastes the Kingdom of God with his spiritual senses. And the Lord Himself says that this Kingdom is within us.

—How can we fulfill the Apostle's command: "Be joyful at all times" and acquire true spiritual joy?

—When a monk gradually obtains constant communion with God, the fruits of this communion will be joy. True joy is not a psychological but a spiritual state. St. Nectarios, a great saint of our times, put it very well in a letter he wrote: He who seeks sources of joy within himself has gone astray, and is in a state of delusion. For example, one person we love, comes from abroad to our monastery. Naturally, we rejoice that he is with us. But as much as we rejoice in his presence, we equally grieve when he leaves. We can take this thought further. We love a certain person, but God takes him from us and he leaves this life, and the love we had for him turns into equal pain after his death. Therefore, a person should not absolutize the joys that are outside of him. The source of joy is in his heart; it is the constant presence of grace. Therefore a man of God is always peaceful and calm at both joyful and sad events.

—How can we unite the commandment of love for neighbor with the obligation to be concentrated and silent?

—Here also discernment is needed, because we often fall into extremes. For example, one of our brothers in the monastery did not have a very good voice. I said to him, "You know, son, don't sing in the catholicon (the main church), but sing in our smaller churches, with three or four other fathers". So he came one day to sing; there were four of them, but then the cook came and then there were five. The brother stopped singing and said to the cook, "Either you or me." The cook was surprised. "Why?" he said. The brother answered, "The Elder blessed me to sing only when there were up to four brothers in the choir." What am I trying to say? We must have a correct understanding of our spiritual father's commandments. We have to know when to talk and when to be silent. After all, silence can come from egoism, or neurasthenia; but there is also spiritual silence. I once asked my monks not to talk during services. So, during a service, one brother came up to another brother and asked him about something to do with the kitchen, and instead of answering him, the other showed him by a gesture that it is forbidden to talk (he placed his finger over his lips). This is not obedience. He was obligated to answer because this was something necessary. But when a monk loves silence, God gives him the opportunity and the time to be silent.

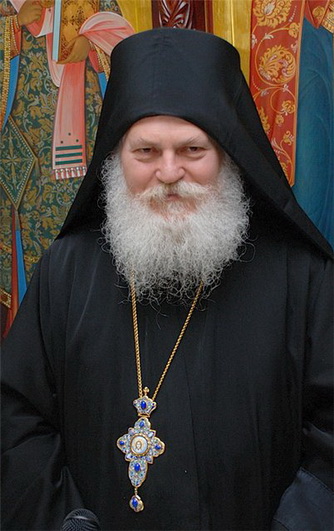

Elder Ephraim of Vatopaidi

Therefore, my dear ones, it is a great blessing that we have come to monasticism. Our elder Joseph of Vatopedi of blessing repose very often said to us, "There is no greater blessing for a person than when God calls him to the monastic life. May the monk never, not even for a second, ever forget that God Himself called him." When we remember how we left the world, what went along with us then, we see that God's grace was upon us, that it accomplished our renunciation of the world, and led us to the monastery. Here we must fulfill three virtues in their entirety: non-acquisitiveness, obedience, and chastity. These virtues lead us in the spiritual life, root us in it, and help us attain the fullness of maturity in Christ.

Monasticism is the path of perfection, and therefore we monastics are called to acquire the fullness of grace. Not long ago, one monk came to me and said, "You know, I have no time to read." I said to him, "My child, the monastery is not a place of reading. You have come to the monastery not to read, and not even to pray. You have come to deny yourself and submit yourself to spiritual guidance. If you give yourself over in obedience to the abbot and not try to get as comfortable as possible in this life, then you will fulfill Christ's commandment exactly. He never said anything accidently, but always unmistakenly, and He said to us monks: Whoever will come after me, let him take up his cross and follow Me."

Whoever in the monastery fulfills his own desires and dreams is not denying himself. A monk should not have any dreams at all—no ambitions or plans. He comes as a man condemned to death, lifts his arms and says to the abbot, "Do with me as you will." By this he fulfills another of Christ's words: "He who wants to save his own soul will lose it." And if a monk understands the meaning of these words and places them at the foundation of his life, he will have a correct understanding of podvig, and all his problems will be solved. He becomes an organ of God's Providence and fully imitates our Lord Jesus Christ, Who, although sinless, came and stood on the level of us penitents, as if He also needed repentance. Christ did not just give commandments from the heavens for us to observe; He Himself came to us and demonstrated them to us in practice. And what did He say to us, absolutely clearly? "I have come not to do my own will, but the will of my Father Who sent Me." Our blessed elder Joseph told us in his talks, "What do you think, brothers: if Christ were to fulfill His own will—would that have been sinful? Nevertheless, He did not do that, so that He could be One Who first does, and then teaches." Man's will and desire is a brass wall. Not a clay, not a stone, not a cement, but a brass wall separating him from God. Blessed is the monk who obeys. Obedience is not a discipline; it is something different. Obedience is when you give over your heart. Monastic life is fully Christ-centered. Therefore the elder does not use his spiritual children's obedience for his own purposes. His task is to convince the monk to submit his will to the will of God.

If you have any questions, ask them and I will answer them if I can.

—How can one notice the appearance of a sinful thought, and cut off in time a passionate thought that infect us while it is still at the state of suggestion?

—Do not be over-preoccupied with thoughts—they need to be treated with disdain. One monk in our monastery once came to me and said, "I need to confess." I saw that he was carrying a notebook. I asked him, "What is that you have?" "It is my confession," he answered. "Well, give it to me," I said. "I will read your notebook." Just imagine—thirty pages of thoughts! I said to him, "Do you think you need to confess every thought that comes into your head? You'll end up in a psychiatric hospital that way!" He had written down even the thoughts that came to him during services. I told this brother, "Thoughts that come in do not mean anything." Even if the mind inclines toward them for a moment, this does not mean anything, absolutely nothing! Forget them! You need to confess only those thoughts that do not go away for a long time, that stay in the mind for days or weeks; but in general thoughts are soap bubbles.

I will tell you about yet another incident from life. One young man, a church-going man, fell into gluttony—he wanted to eat a shish kebob on a Wednesday, and went to buy it. He came to the store and the salesman said, "Forgive me but I just sold the last one." This young man then came to me and said, "This is what happened, and I would have eaten a shish kebob!" I said to him, "But you did not eat it? That is all! You gave in to a thought, but did not sin in deed." How is it with us? First there is the thought, and then it becomes a word, and then a deed. But a sin is considered committed when it becomes a deed. Therefore, be attentive and do not be preoccupied much with thoughts; disdain them. "For the thoughts of mortal men are miserable" (Wis. 9:14), literally, "Thoughts are cowardly"

—Fr. Ephraim, to what do you think monastics in Russia should be paying particular attention, so that our monasteries would be stronger and flourish?

—You need to pay attention to obedience. A monk should obey and not have passionate attachments; this especially relates to women monastics. I have one women's monastery, and when I go there, it all begins: "Geronda, pray for my aunt, my nephew, my nephew's neighbor. Geronda, pray for my brother, for my sister's friend." You shouldn't be concerned with your aunt's, your nephews' or their neighbors' needs. Pay attention to this, because the virtue of exile is particularly hard for women; they tend to be very attached to their relatives. They start praying fervently for them, but under the guise of prayer for their relatives, their hearts cleave to them again. Obedience, however, tells us to give ourselves wholly to Christ. Whoever does not renounce his property, says the Lord, cannot be my disciple. These are the words of Christ, Who was merciful, Who was a teacher of mercy! But do you remember what the man said after the Savior called him to follow Him? "Allow me to go and bury my father." He was not lying, after all; he would have done just that. But Christ said, "No let the dead bury their dead. You follow Me." Why do you think He said that? Because man's mind is called to illumination, and compared to this illumination, this sanctity, everything is insignificant, nothing. Or, for example, many people write letters to their relatives who are monks. The brothers ask me, "Geronda, should I answer the letter?" "No," I say, "you don't need to answer it. Pray for them, and that will be your greatest offering."

—How can a complicated and responsible monastic job having to do with monastery property management be combined with the commandment not to care for tomorrow?

—Whoever cares for these things is doing them in obedience—he has a "carefree care". St. Silhouan the Athonite was the steward, not even of the monks, but of the lay workers. At the same time he was a great man of silence, a true hesychast. Pay attention to this! Do you remember how he himself admitted in his recollections: "The abbot told me to be the steward of the workers, and I inwardly resisted. 'Oh, father, what are you burdening me with…'" He did not accept it right away only inwardly, and did not show swift obedience, although he went and did this job. But the level of his spiritual progress did not allow him the right to resist even inwardly. He himself admitted that for this resistance against the abbot he had headaches his whole life as a penance. So, be very careful. Look at how Christ mysteriously, in an amazing way equated the will of a lawful organ—that is, the abbot—with His own will. What does He say? "Whoever hears you hears Me, and whoever rejects you rejects Me." Therefore, another great saint of our times, Elder Porphyrius of Kavsokalyvia, emphasized the significance of joyful obedience.

—How can repentance be combined with spiritual joy, compunction and inner peace? Both are needed, but apparently contradict each other.

—To the extent that a person repents and has that inner lamentation commanded by Christ, he will feel simultaneously that this lamentation is joy-producing. Do not contemplate spiritual things by using the feelings or sentimentality. One may weep because he has a psychological problem, another weeps from sentimentality, while a third weeps for spiritual reasons. Unfortunately, we have not worthily responded to God's call—I am speaking of myself—and we do not measure up to God's grace and long-suffering for us. But we have known holy elders, our contemporaries, who had compassion for people and prayed for everyone with great pain of heart. They were always peaceful, joyful, and easy to be around. This is the wonder of a spiritual person.

—Do you think that the monastic virtues of the ancient fathers are possible in modern monasticism?

—Both monasticism and man have always been the same throughout all times. Of course, people of the twenty-first century unfortunately do not have the same self-mastery or strength as the ancients had. But if a person wants this, he can labor in asceticism according to his strength and experience the same grace as did the ancient fathers.

—How can we avoid depression when repenting? Where is the boundary between repentance and depression?

—In order to help us discern this, we have spiritual guides. One day a nun came to elder Porphyrius, who was clairvoyant. She had read much about remembrance of death and had begun to feel depressed from it, because it was beyond her strength. As soon as the elder saw this nun he could immediately see what the problem was. Before she even said anything, he said to her, "You do not have a blessing to exercise the remembrance of death. Think only about Christ's love." Thus, the podvig of repentance should be directed by a spiritual guide who looks at each person's spiritual state. When my elder, Joseph of Vatopedi, was young, he put much effort into self-criticism and began to get depressed because of it. Then our "grandfather", Joseph the Hesychast, said to him, "Son, work with this—but only a little, not too heavily." Of course, after maturing spiritually he had no problem with this practice.

It is because the spiritual state of the monk must be observed that the holy fathers prescribed that the spiritual father, the abbot, be always in the monastery. Of course, he can be absent for a few days, but in general he is continually with the brothers. Our laypeople, for example, see their spiritual father once or twice a month, the more reverent ones once a month; continual association with a spiritual father is not for them. But the holy fathers did institute this for monks because monks are as if walking a tightrope, and they need continual help.

—How can we discern salvific memory of death from ordinary fear of death, which even non-religious people feel?

—One person told me that he used to be very afraid of death. After he began coming to Mt. Athos, this fear disappeared completely. God gave him such a gift. Psychological fear is not a good fear; it rejects [death], but remembrance of death in Christ is victory over death.

Once a group of pilgrims came to our monastery, and after Compline I talked with them a little. I do not know why, but I began to talk with them about remembrance of death. There was one psychologist among them. He said to me later, "Father, we came to you on the Holy Mountain, and you began talking to us about such sad things." At first I did not understand what had happened. He then said, "Couldn't you have found something else to talk about? Why talk about death?" He was continually tapping his wooden armchair—a superstitious action against the evil eye. However, remembrance of death in Christ does not cause depression in people—it fills them with joy. After all, in Christ we conquer death, and pass over from death into life! We monks are the heralds of eternal life. Why? Because we already have a presentiment of the Kingdom of God in our hearts. Do you remember what Abba Isaiah said? "Remember the Kingdom of Heaven, and it will draw you in little-by-little." That is why a monk is always joyful. He already tastes the Kingdom of God with his spiritual senses. And the Lord Himself says that this Kingdom is within us.

—How can we fulfill the Apostle's command: "Be joyful at all times" and acquire true spiritual joy?

—When a monk gradually obtains constant communion with God, the fruits of this communion will be joy. True joy is not a psychological but a spiritual state. St. Nectarios, a great saint of our times, put it very well in a letter he wrote: He who seeks sources of joy within himself has gone astray, and is in a state of delusion. For example, one person we love, comes from abroad to our monastery. Naturally, we rejoice that he is with us. But as much as we rejoice in his presence, we equally grieve when he leaves. We can take this thought further. We love a certain person, but God takes him from us and he leaves this life, and the love we had for him turns into equal pain after his death. Therefore, a person should not absolutize the joys that are outside of him. The source of joy is in his heart; it is the constant presence of grace. Therefore a man of God is always peaceful and calm at both joyful and sad events.

—How can we unite the commandment of love for neighbor with the obligation to be concentrated and silent?

—Here also discernment is needed, because we often fall into extremes. For example, one of our brothers in the monastery did not have a very good voice. I said to him, "You know, son, don't sing in the catholicon (the main church), but sing in our smaller churches, with three or four other fathers". So he came one day to sing; there were four of them, but then the cook came and then there were five. The brother stopped singing and said to the cook, "Either you or me." The cook was surprised. "Why?" he said. The brother answered, "The Elder blessed me to sing only when there were up to four brothers in the choir." What am I trying to say? We must have a correct understanding of our spiritual father's commandments. We have to know when to talk and when to be silent. After all, silence can come from egoism, or neurasthenia; but there is also spiritual silence. I once asked my monks not to talk during services. So, during a service, one brother came up to another brother and asked him about something to do with the kitchen, and instead of answering him, the other showed him by a gesture that it is forbidden to talk (he placed his finger over his lips). This is not obedience. He was obligated to answer because this was something necessary. But when a monk loves silence, God gives him the opportunity and the time to be silent.

Elder Ephraim of Vatopaidi